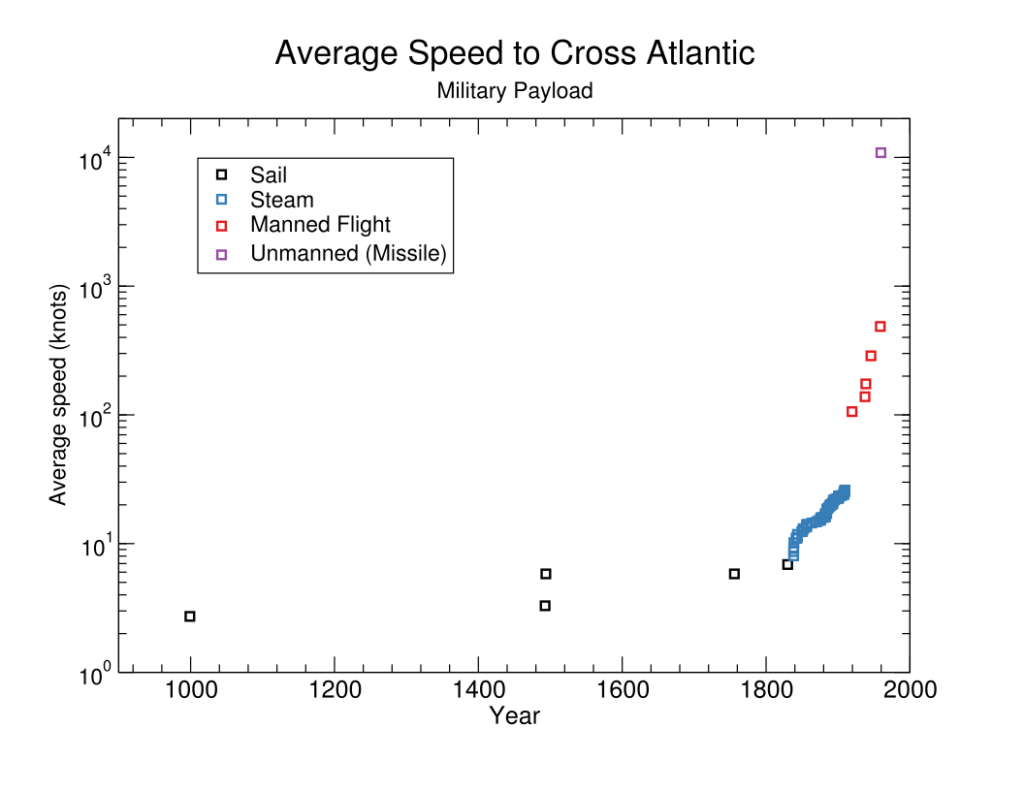

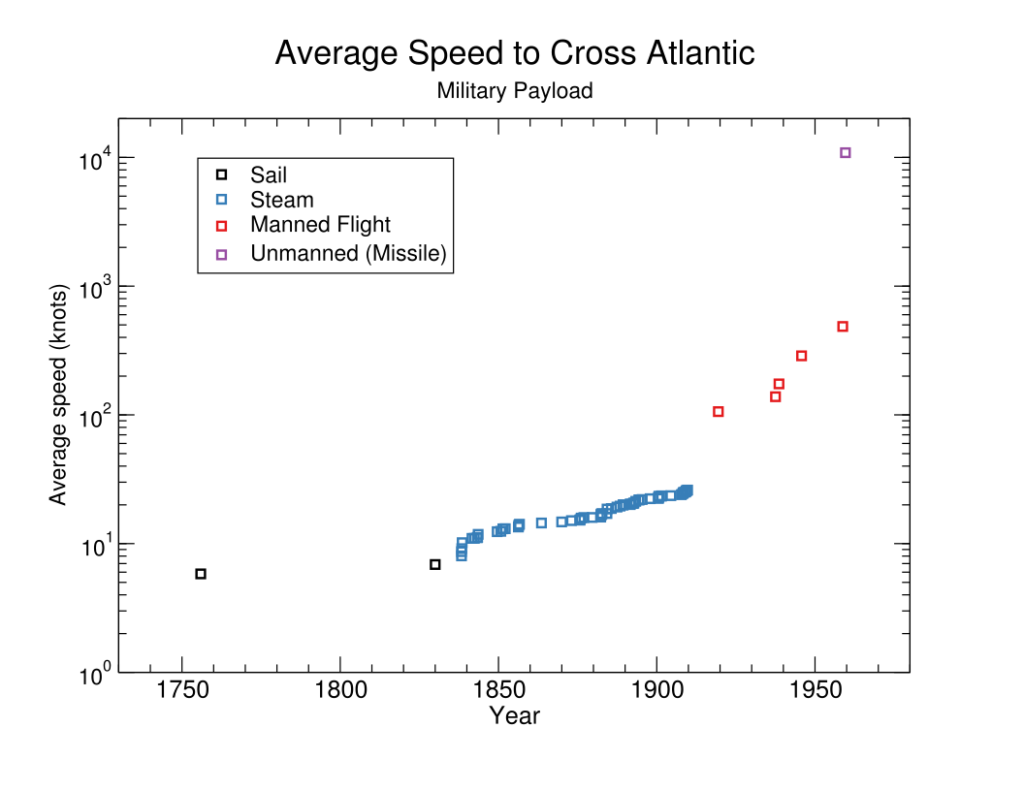

The speed at which a military payload could cross the Atlantic ocean contained six greater than 10-year discontinuities in 1493 and between 1841 and 1957:

| Date | Mode of transport | Knots | Discontinuity size (years of progress at past rate) |

| 1493 | Columbus’ second voyage | 5.8 | 1465 |

| 1884 | Oregon | 18.6 | 10 |

| 1919 | WWI Bomber (first non-stop transatlantic flight) | 106 | 351 |

| 1938 | Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor | 174 | 19 |

| 1945 | Lockheed Constellation | 288 | 25 |

| 1957 | R-7 (ICBM) | ~10,000 | ~500 |

Details

Background

The speed at which a weapons payload could be delivered to a target on the opposite side of the ocean appears to have been limited to the speed of a piloted vehicle (and so coincided with speed of passenger delivery) until the first long-range missiles became available in the late 1950s.1.

Trends

This case study is part of AI Impacts’ discontinuous progress investigation.

Transatlantic military payload delivery speed

We look at fastest speeds of real historic systems that could have delivered military payloads across the Atlantic Ocean. We do not require that any military payload was actually sent by the method in question.

We generally use whatever route was actually taken (or supposed in an estimate), and do not attempt to infer faster speeds possible had an optimal route been taken (though note that because we are measuring speed rather than time to cross the Ocean, route length is adjusted for to a first approximation).

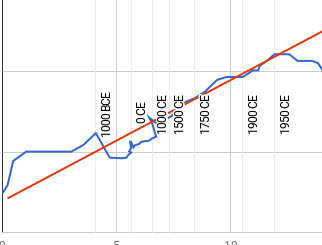

We only investigated this metric from 1492-1493 and 1841-1957. We do not investigate 1493-1841 because our data is insufficiently complete to determine how continuous it was.2

Data

We collated records of historic potential times to cross the Atlantic Ocean for military payloads. These are available at the ‘Payload’ tab of this spreadsheet, and are displayed in Figure 1 and 2 below. We have not thoroughly verified this data.

Because military payload delivery coincided with passenger travel until the late 1950s, most of our data coincides with that used in our investigation into historic trends in transatlantic passenger travel.

The advent of ICBMs in 1957 probably increased the crossing speed to thousands of knots. We are fairly uncertain about how fast the first ICBMs were, but our impression is that they traveled at an average of least 5,000 knots and likely more like 10,000 knots.3 Uncertainty here makes little difference to measurement of discontinuities. To not be a discontinuity of more than a hundred years, the first ICBM would need to have traveled horizontally at less than 2314 knots, which seems unlikely, because that is insufficient speed to cross the ocean, assuming optimal angle of fire.4

We haven’t recorded the later trend, since our understanding is that modern ICBMs do not travel much faster than we think early ones may easily have done.5 so will not yield clear discontinuities, and we do not know of faster missiles than ICBMs.6

Discontinuity measurement

Until 1957, discontinuities are the same as those for speed of transatlantic passenger travel, since the data coincides. This gives us five discontinuities.

We calculate the final development, the ICBM, to probably represent a discontinuity of around 500 years, but at least 1007. See this spreadsheet, tab ‘Payload’ for our calculation.8

This gives us six greater than 10-year discontinuities in total, including five shared with transatlantic passenger travel speed. Three of them represent more than one hundred years of past progress:

| Date | Mode of transport | Knots | Discontinuity size (years of progress at past rate) |

| 1493 | Columbus’ second voyage | 5.8 | 1465 |

| 1884 | Oregon | 18.6 | 10 |

| 1919 | WWI Bomber (first non-stop transatlantic flight) | 106 | 351 |

| 1938 | Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor | 174 | 19 |

| 1945 | Lockheed Constellation | 288 | 25 |

| 1957 | R-7 (ICBM) | ~10,000 | ~500 |

In addition to the sizes of these discontinuity in years, we have tabulated a number of other potentially relevant metrics here.9

Notes

- If there was a pilotless way to quickly cross the Atlantic prior to ICBMs we have not been able to find it.

- See historic trends in transatlantic passenger travel for discussion of this.

- Some evidence:

- The first ICBM to successfully travel an intercontinental distance, R-7, was initially planned to travel at 13,000 knots.

- Our impression is that a typical ICBM flight trajectory is mostly free-fall and that most missiles were launched on trajectories that are optimally fuel efficient, which means ballistic missiles should have similar average flight times over similar distances. Later ICBMs seem to generally travel at speeds of at least 10,000 knots (though we are unsure whether this is horizontal motion or also includes vertical motion).

- Under projectile motion ignoring the curvature of the Earth, optimal angle of fire is 45 degrees, so 2314 knots of horizontal motion means 3269 knots of angular motion. At that speed, the projectile travels less than 300km. Over 300km, the curvature of the Earth is not enough to substantially change this trajectory, or in particular make it twenty times as long.

- For instance, this 2013 list of longest range ICBMs mentions a missile that cruises at 15,000mph:

“The solid-fuelled propulsion system ensures the missile to cruise at a speed of 15,000mph (24,140km/h).”

Army Technology. “Longest Range Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles (ICBM): The Top 10 Ranked,” November 3, 2013. https://www.army-technology.com/features/feature-the-10-longest-range-intercontinental-ballistic-missiles-icbm/.

- Cruise missiles are much slower. For instance, BrahMos is purportedly the fastest supersonic cruise missile, and can travel at mach 2.8 or 1867 knots.

“It can gain a speed of Mach 2.8…”“BrahMos.” In Wikipedia, November 27, 2019. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=BrahMos&oldid=928133032.

- See above for why it must be at least 100 years

- See methodology for discontinuity investigation for more details. For instance, for the purpose of evaluating each point relative to past progress, we treat the data as several different linear or exponential trends. The methodology page describes how we decide what to treat as the trend of ‘past progress’ for each point.

- See our methodology page for more details.