Katja Grace, 9 September 2021

[Content warning: death in fires, death in machine apocalypse]

‘No fire alarms for AGI’

Eliezer Yudkowsky wrote that ‘there’s no fire alarm for Artificial General Intelligence’, by which I think he meant: ‘there will be no future AI development that proves that artificial general intelligence (AGI) is a problem clearly enough that the world gets common knowledge (i.e. everyone knows that everyone knows, etc) that freaking out about AGI is socially acceptable instead of embarrassing.’

He calls this kind of event a ‘fire alarm’ because he posits that this is how fire alarms work: rather than alerting you to a fire, they primarily help by making it common knowledge that it has become socially acceptable to act on the potential fire.

He supports this view with a great 1968 study by Darley and Latané, in which they found that if you pipe a white plume of ‘smoke’ through a vent into a room where participants fill out surveys, a lone participant will quickly leave to report it, whereas a group of three (innocent) participants will tend to sit by in the haze for much longer1.

Here’s a video of a rerun2 of part of this experiment, if you want to see what people look like while they try to negotiate the dual dangers of fire and social awkwardness.

A salient explanation for this observation3 is that people don’t want to look fearful, and are perhaps repeatedly hit by this bias when they interpret one another’s outwardly chill demeanor as evidence that all is fine. (Darley and Latané favor a similar hypothesis, but where people just fail to interpret a stimulus as possibly dangerous if others around them are relaxed.)

So on that hypothesis, thinks Eliezer, fire alarms can cut past the inadvertent game of chicken produced by everyone’s signaling-infused judgment, and make it known to all that it really is fire-fleeing time, thus allowing face-saving safe escape.

With AI, Eliezer thinks people are essentially sitting by in the smoke, saying ‘looks fine to me’ to themselves and each other to avoid seeming panicky. And so they seem to be in need the analogue of a fire alarm, and also (at least implicitly) seem to be expecting one: assuming that if there were a real ‘fire’, the fire alarm would go off and they could respond then without shame. For instance, maybe new progress would make AI obviously an imminent risk to humanity, instead of a finicky and expensive bad writing generator, and then everyone would see together that action was needed. Eliezer argues that this isn’t going to happen—and more strongly (though confusingly to me) that things will look basically similar until AGI—and so he seems to think that people should get a grip now and act on the current smoke or they will sit by forever.

My take

I forcefully agree with about half of the things in that post, but this understanding of fire alarms—and the importance of there not being one for AGI—is in the other half.

It’s not that I expect a ‘fire alarm’ for AGI—I’m agnostic—it’s just that fire alarms like this don’t seem to be that much of a thing, and are not how we usually escape dangers—including fires—even when group action is encumbered by embarrassment. I doubt that people are waiting for a fire alarm or need one. More likely they are waiting for the normal dance of accumulating evidence and escalating discussion and brave people calling the problem early and eating the potential embarrassment. I do admit that this dance doesn’t look obviously up to the challenge, and arguably looks fairly unhealthy. But I don’t think it’s hopeless. In a world of uncertainty and a general dearth of fire alarms, there is much concern about things, and action, and I don’t think it is entirely uncalibrated. The public consciousness may well be oppressed by shame around showing fear, and so be slower and more cautious than it should be. But I think we should be thinking about ways to free it and make it healthy. We should not be thinking of this as total paralysis waiting for a magical fire alarm that won’t come, in the face of which one chooses between acting now before conviction, or waiting to die.

To lay out these pictures side by side:

Eliezer’s model, as I understand it:

- People generally don’t act on a risk if they feel like others might judge their demonstrated fear (which they misdescribe to themselves as uncertainty about the issue at hand)

- This ‘uncertainty’ will continue fairly uniformly until AGI

- This curse could be lifted by a ‘fire alarm’, and people act as if they think there will be one

- ‘Fire alarms’ don’t exist for AGI

- So people can choose whether to act in their current uncertainty or to sit waiting until it is too late

- Recognizing that the default inaction stems not from reasonable judgment, but from a questionable aspect of social psychology that does not appear properly sensitive to the stakes, one should choose to act.

My model:

- People act less on risks on average when observed. Across many people this means a slower ratcheting of concern and action (but way more than none).

- The situation, the evidence and the social processing of these will continue to evolve until AGI.

- (This process could be sped up by an event that caused global common knowledge that it is socially acceptable to act on the issue—assuming that that is the answer that would be reached—but this is also true of Eliezer having mind control, and fire alarms don’t seem that much more important to focus on than the hypothetical results of other implausible interventions on the situation)

- People can choose at what point in a gradual escalation of evidence and public consciousness to act

- Recognizing that the conversation is biased toward nonchalance by a questionable aspect of social psychology that does not appear properly sensitive to the stakes, one should try to adjust for this bias individually, and look for ways to mitigate its effects on the larger conversation.

(It’s plausible that I misunderstand Eliezer, in which case I’m arguing with the sense of things I got from misreading his post, in case others have the same.)

If most people at some point believed that the world was flat, and weren’t excited about taking an awkward contrarian stance on the topic, then it would indeed be nice if an event took place that caused basically everyone to have common knowledge that the world is so blatantly round that it can no longer be embarrassing to believe it so. But that’s not a kind of thing that happens, and in the absence of that, there would still be a lot of hope from things like incremental evidence, discussion, and some individuals putting their necks out and making the way less embarrassing for others. You don’t need some threshold being hit, or even a change in the empirical situation, or common knowledge being produced, or or all of these things at once, for the group to become much more correct. And in the absence of hope for a world-is-round alarm, believing that the world is round in advance because you think it might be and know that there isn’t an alarm probably isn’t the right policy.

In sum, I think our interest here should actually be on the broader issue of social effects systematically dampening society’s responses to risks, rather than on ‘fire alarms’ per se. And this seems like a real problem with tractable remedies, which I shall go into.

I. Do ‘fire alarms’ show up in the real world?

Claim: there are not a lot of ‘fire alarms’ for anything, including fires.

How do literal alarms for fires work?

Note: this section contains way more than you might ever want to think about how fire alarms work, and I don’t mean to imply that you should do so anyway. Just that if you want to assess my claim that fire alarms don’t work as Eliezer thinks, this is some reasoning.

Eliezer:

“One might think that the function of a fire alarm is to provide you with important evidence about a fire existing, allowing you to change your policy accordingly and exit the building.

In the classic experiment by Latane and Darley in 1968, eight groups of three students each were asked to fill out a questionnaire in a room that shortly after began filling up with smoke. Five out of the eight groups didn’t react or report the smoke, even as it became dense enough to make them start coughing. Subsequent manipulations showed that a lone student will respond 75% of the time; while a student accompanied by two actors told to feign apathy will respond only 10% of the time. This and other experiments seemed to pin down that what’s happening is pluralistic ignorance. We don’t want to look panicky by being afraid of what isn’t an emergency, so we try to look calm while glancing out of the corners of our eyes to see how others are reacting, but of course they are also trying to look calm…

…A fire alarm creates common knowledge, in the you-know-I-know sense, that there is a fire; after which it is socially safe to react. When the fire alarm goes off, you know that everyone else knows there is a fire, you know you won’t lose face if you proceed to exit the building.

The fire alarm doesn’t tell us with certainty that a fire is there. In fact, I can’t recall one time in my life when, exiting a building on a fire alarm, there was an actual fire. Really, a fire alarm is weaker evidence of fire than smoke coming from under a door.

But the fire alarm tells us that it’s socially okay to react to the fire. It promises us with certainty that we won’t be embarrassed if we now proceed to exit in an orderly fashion.”

I don’t think this is actually how fire alarms work. Which you might think is a nitpick, since fire alarms here are a metaphor for AI epistemology, but I think it matters, because it seems to be the basis for expecting this concept of a ‘fire alarm’ to show up in the world. As in, ‘if only AI risk were like fires, with their nice simple fire alarms’.

Before we get to that though, let’s restate Eliezer’s theory of fire response behavior here, to be clear (most of it also being posited but not quite favored by Darley and Latané):

- People don’t like to look overly scared

- Thus they respond less cautiously to ambiguous signs of danger when observed than when alone

- People look to one another for evidence about the degree of risk they are facing

- Individual underaction (2) is amplified in groups via each member observing the others’ underaction (3) and inferring greater safety, then underacting on top of that (2).

- The main function of a fire alarm is to create common knowledge that the situation is such that it is socially acceptable to take a precaution, e.g. run away.

I’m going to call hypotheses in the vein of points 1-4 ‘fear shame’ hypotheses.

fear shame hypothesis: the expectation of negative judgments about fearfulness ubiquitously suppress public caution.

I’m not sure about this, but I’ll tentatively concede it and just dispute point 5.

Fire alarms don’t solve group paralysis

A first thing to note is that fire alarms just actually don’t solve this kind of group paralysis, at least not reliably. For instance, if you look again closely at the rerun of the Darley and Latané experiment that I mentioned above, they just actually have a fire alarm4, as well as smoke, and this seems to be no impediment to the demonstration:

The fire alarm doesn’t seem to change the high level conclusion: the lone individual jumps up to investigate, and the people accompanied by a bunch of actors stay in the room even with the fire alarm ringing.

And here is a simpler experiment entirely focusing on what people do if they hear a fire alarm:

Answer: these people wait in place for someone to tell them what to do, many getting increasingly personally nervous. The participant’s descriptions of this are interesting. Quite a few seem to assume that someone else will come and lead them outside if it is important.

Maybe it’s some kind of experiment thing? Or a weird British thing? But it seems at least fairly common for people not to react to fire alarms. Here are a recent month’s tweets on the topic:

Lmaoo the fire alarm is going off in Newark Airport and everyone is ignoring it

— andy (@Andy_Val16) August 21, 2021

Ignoring my fire alarm once again 👍

— Socks 🏳️🌈🏳️⚧️ (@SockTheDogThing) August 16, 2021

Fire alarm is going off in my building and only like 5 people are outside. So everyone is just ignoring the emergency.? There’s a fire btw)

— Gary? (@ProbsArmenian) August 17, 2021

I’m mad we really all just ignoring this fire alarm at the hospital 🤣

— ROXANNE🤍✨ (@medicyn22) August 13, 2021

That’s the fire alarm going off again with the @WFANmornings in the background. I guess we’re just ignoring the fire alarm it keeps going off. #safeworkplace #ignorethealarm pic.twitter.com/uTc03ko7PI

— ⚾ Matt M ⚾ (@MetsFanMatthew) August 11, 2021

Had our fire alarms going off at work and I knew that one of our directors was having a meeting. I interrupted the meeting of men ignoring the fire alarm and I said they had to get out of the building. They hesitated, I persisted. The meeting was with town fire marshal reps.

— Chris Keleher-Pierce (@Acoustic1234) August 5, 2021

Howard girls ignoring the Quad fire alarm every day https://t.co/gQaUdJ4unn

— Treye🤍𓅗 (@treye_ovo) August 3, 2021

one day there’s gonna be a real fire at my complex & ima be sitting here ignoring it bc the alarm goes off so casually

— Lana Bologna (@lanabologna) August 3, 2021

It’s the fire alarm going on , and me completely ignoring it

— Zu (@Zuzile_Zu) July 25, 2021

A fire alarm went off in the subway station this morning and everyone just stood there ignoring it and carried on their day like nothing happened. Cant help thinking this is essentially Japan’s COVID19 response.

— Tom Kelly ケリー・トム (@tomkXY) May 20, 2021

The first video also suggests that the 1979 Woolworths fire killed ten people, all in the restaurant, because those people were disinclined to leave before paying their bill, due to a similar kind of unwillingness to diverge from normal behavior. I’m not sure how well supported that explanation is, but it seems to be widely agreed that ten people died, all in the restaurant, and that people in the restaurant had been especially unwilling to leave under somewhat bizarre circumstances (for instance, hoping to finish their meals anyway5, or having to be dragged out against their will6). According to a random powerpoint presentation I found on the internet, the fire alarm went off for four minutes at some point, though it’s possible that at that point they did try to leave, and failed. (The same source shows that all were found quite close to the fire escape, so they presumably all tried to leave prior to dying, but that probably isn’t that surprising.) This seems like probably a real case of people hearing a fire alarm and just not responding for at least some kind of weird social reasons, though maybe the fire alarm was just too late. The fact that everyone else in the 8 floor building managed to escape says there was probably some kind of fairly clear fire evidence.

So, that was a sequence of terrifying demonstrations of groups acting just like they did in the Darley and Latané experiment, even with fire alarms. This means fire alarms aren’t an incredibly powerful tool against this problem. But maybe they make a difference, or solve it sometimes, in the way that Eliezer describes?

How might fire alarms work? Let’s go through some possible options.

By creating common knowledge of something to do with fire?

This is Eliezer’s explanation above. One issue with it is that given that fire alarms are so rarely associated with fires (as Eliezer notes) the explanation, ‘A fire alarm creates common knowledge, in the you-know-I-know sense, that there is a fire…’ seems like it must be a markedly different from the precise mechanism. But if a fire alarm is not producing common knowledge of a fire, what is it producing common knowledge of, if anything?

…common knowledge of the fire alarm itself?

Fire alarms might produce common knowledge that there’s a fire alarm going off better than smoke produces common knowledge of smoke, since fire alarms more aggressively observable, such that hearing one makes it very likely that others can hear it and can infer that you can hear it, whereas smoke can be observed more privately, especially in small quantities. Even if you point out the smoke in an attempt to create common knowledge, other people might think that you are mistaking steam for smoke due to your fear-tainted mindset. Smoke is more ambiguous. In the experiments, people who didn’t leave—seemingly due to being in groups—reportedly attributed their staying to the smoke probably not being smoke (which in fairness it wasn’t). Fire alarms are also ambiguous, but maybe less so.

But it’s not obvious how common knowledge of the fire alarm itself avoids the problem, since then everyone has to judge how dire a threat a fire alarm is, and again one can have more and less fear-indicative choices.7

…common knowledge of some low probability of fire?

A perhaps more natural answer is that fire alarms produce common knowledge ‘that there is some non-negligible risk of fire, e.g. 1%’. This would be an interesting model, because if Eliezer is right that fire alarms rarely indicate fires and are probably less evidence of a fire than smoke8 then it must be that a) fire alarms produce common knowledge of this low chance of fire while smoke fails to produce common knowledge of a higher chance of fire, and b) common knowledge of a low risk is worth leaving for, whereas non-common knowledge of a higher risk is not worth leaving for.

These both make sense in theory, strictly speaking:

- Fire alarms are intrinsically more likely to produce common knowledge (as described above)

- People might have a more shared understanding of the probability of fire implied by a fire alarm than of the probability of fire implied by smoke, so that common knowledge of smoke doesn’t produce common knowledge of an n% chance of danger but common knowledge of a fire alarm does.

- If you think there is a 5% risk of fire but that your friends might mistake you for thinking that there is a 0.01% risk of fire, then you might be less keen to leave than if you all have common knowledge of a 1% risk of fire.

But in practice, it seems surprising to me if this is a good description of what’s going on. Some issues:

- Common knowledge doesn’t seem that unlikely in the smoke case, where others are paying enough attention to see you leave.

- If others actually don’t notice the smoke, then it’s not clear why leaving should even indicate fear to them at all. For instance, without knowing the details of the experiment in the video, it seems as though if the first woman with company had just quietly stood up and walked out of the room, she should not expect the others to know she is responding to a threat of fire, unless they too see the smoke, in which case they can also infer that she can infer that either they have either seen the smoke too or they haven’t and have no reason to judge her. So what should she be scared of, on a story where the smoke just produces less common knowledge?

- People presumably have no idea what probability of fire a fire alarm indicates, making it very hard for one to create common knowledge of a particular probability of fire among a group of people.

Given these things, I don’t buy that fire alarms send people outside via creating common knowledge of some low probability of fire.

…common knowledge that it isn’t embarrassing?

Another possibility is that the fire alarm produces common knowledge of the brute fact that it is now not embarrassing to leave the building. But then why? How did it become non-embarrassing? Did the fire alarm make it so, or did it respond to the situation becoming non-embarrassing?

…common knowledge of it being correct to leave?

Maybe the best answer in this vicinity is ‘that there is a high enough risk that you should leave’. This sounds very similar to ‘that there is some particular low risk’, but it gloms together the ‘probability of fire’ issue and the ‘what level of risk means that you should leave’ issue. The difference is that if everyone was uncertain about the level of risk, and also about at what level of risk they should leave, the fire alarm is just making a bid for everyone leaving, thereby avoiding the step where they have to make a judgment about under what level of risk to leave, which is perhaps especially likely to be the step at which they might get judged. This also sounds more realistic, given that I don’t think anyone has much idea about either of these steps. Whereas I could imagine that people broadly agree that a fire alarm means that it is leaving time.

On the other hand, if I imagine leaving a building because of a fire alarm, I expect a decent amount of the leaving to be with irritation and assertion that there is not a real fire. Which doesn’t look like common knowledge that it is the risk-appropriate time to leave. Though I guess viewed as a strategy in the game, ‘leave but say you wouldn’t if you weren’t being forced to, because you do not feel fear’ seems reasonable.

In somewhat better evidence-from-imagination, if a fire alarm went off in my house, in the absence of smoke, and I went and stood outside and called the fire brigade, I would fear seeming silly to my housemates and would not expect much company. So I at least am not in on common knowledge of fire alarms being a clear sign that one should evacuate—I may or may not feel that way myself, but I am not confident that others do.

Perhaps a worse problem with this theory is that it isn’t at all clear how everyone would have come to know and/or agree that fire alarms indicate the right time to leave.

I think a big problem for these common knowledge theories in general is that if fire alarms sometimes fail to produce common knowledge that it isn’t embarrassing to escape (e.g. in the video discussed above), then it is hard for them to produce common knowledge most of the time, due to the nature of common knowledge. For instance, if I hear a fire alarm, then I don’t know whether everyone knows that it isn’t embarrassing for me to leave, because I know that sometimes people don’t think that. It could be that everyone immediately knows which case they are in by the nature of the fire alarm, but I at least don’t know explicitly how to tell.

By providing evidence?

Even if fire alarms don’t produce real common knowledge that much, I wouldn’t be surprised if they help get people outside in ways related to signaling and not directly tied to evidence of fire.

For instance, just non-common-but-not-obviously-private evidence could reduce each person’s expected embarrassment somewhat, maybe making caution worth the social risk. That is, if you just think it’s more likely that Bob thinks it’s more likely that you have seen evidence of real risk, that should still reduce the embarrassment of running away.

By providing objective evidence?

Another similar thing that fire alarms might do is provide evidence that is relatively objective and relies little on your judgment, so you can be cautious in the knowledge that you could defend your actions if called to. Much like having a friend in the room who is willing to say ‘I’m calling it – this is smoke. We have to get out’, even if they aren’t actually that reliable. Or, like if you are a hypochondriac, and you want others to believe you, it’s nice to have a good physical pulse oximeter that you didn’t build.9

This story matches my experience at least some. If a fire alarm went off in my house I think I would seem reasonable if I got up to look around for smoke or a fire. Whereas when I get up to look for a fire when I merely smell smoke, I think people often think I’m being foolish (in their defense, I may be a bit overcautious about this kind of thing). So here the fire alarm is helping me take some cautious action that I wanted to take anyway with less fear of ridicule. And I think what it is doing is just offering relatively personal-judgment-independent evidence that it’s worth considering the possibility of a fire, whereas otherwise my friends might suspect that my sense of smell is extremely weak evidence, and that I am foolish in my inclination to take it as such.

So here the fire alarm is doing something akin to the job Eliezer is thinking of—being the kind of evidence that gives me widely acceptable reason to act without having to judge and so place the quality of my judgment on the line. Looking around when there’s a fire alarm is like buying from IBM or hiring McKinsey. But because this isn’t common knowledge, it doesn’t have to be some big threshold event—this evidence can be privately seen and can vary by person in their situation. And it’s not all or nothing. It’s just a bit helpful for me to have something to point to. With AI, it’s better if I can say ‘have you seen GPT-3 though? It’s insane’ than if I just say ‘it seems to me that AI is scary’. The ability of a particular piece of evidence to do this in a particular situation is on a spectrum, so this is unlike Eliezer’s fire alarm in that it needn’t involve common knowledge or a threshold. There is plenty of this kind of fire alarm for AI. “The median ML researcher says there is a 5% chance this technology destroys the world or something equivalently bad”, “AI can write code”, “have you seen that freaking avocado chair?”.

My guess is that this is more a part of how fire alarms work than anything like genuine common knowledge is.

Another motivation for leaving beside your judgment of risk?

An interesting thing about the function of objective evidence in the point above is that it is not actually much to do with evidence at all. You just need a source of motivation for leaving the building that is clearly not very based on your own sense of fear. It can be an alarm telling you that the evidence has mounted. But it would also work if you had a frail mother who insisted on being taken outside at the first sign of smoke. Then going outside could be a manifestation of familial care rather than anything about your own fear. If the smell of smoke also meant that there were beers outside, that would also work, I claim.

Some other examples I predict work:

- If you are holding a dubiously covid-safe party and you actually want people who are uncomfortable with the crowding to go outside, then put at least one other thing they might want outside, so that they can e.g. wander out looking for the drinks instead of having to go and stand there in fear.

- If you want people in a group who don’t really feel comfortable snorkeling to chicken out and not feel pressured, then make salient some non-fear costs to snorkeling, e.g. that each additional person who does it will make the group a bit later for dinner.

- If you want your child to avoid reckless activities with their friends, say you’ll pay them $1000 if they finish high school without having done those things. This might be directly motivating, but it also gives them a face-saving thing they can say to their friends if they are ever uncomfortable.

This kind of thing seems maybe important.

By authority?

A common knowledge story that feels closer to true to me is that fire alarms produce common knowledge that you are ‘supposed to leave’, at least in some contexts.

The main places I’ve seen people leave the building upon hearing a fire alarm is in large institutional settings—dorms and schools. It seems to me that in these cases the usual thing they are responding to is the knowledge that an authority has decided that they are ‘supposed to’ leave the building now, and thus it is the default thing to do, and if they don’t, they will be in a conflict with for instance the university police or the fire brigade, and there will be some kind of embarrassing hullabaloo. On this model, what could have been embarrassment at being overly afraid of a fire is averted by having a strong incentive to do the fire-cautious action for other reasons. So this is a version of the above category, but I think a particularly important one.

In the other filmed experiment, people were extremely responsive to a person in a vest saying they should go, and in fact seemed kind of averse to leaving without being told to do so by an authority.

With AI risk, the equivalent of this kind of fire alarm situation would be if a university suddenly panicked about AI risk sometimes, and required that all researchers go outside and work on it for a little bit. So there is nothing stopping us from having this kind of fire alarm, if any relevant powerful institution wanted it. But there would be no reason to expect it to be more calibrated than random people about actual risk, much as dorm fire alarms are not more calibrated than random people about whether your burned toast requires calling the fire brigade. (Though perhaps this would be good, if random caution is better than consistent undercaution.)

Also note that this theory just moves the question elsewhere. How do authorities get the ability to worry about fires, without concern for shame? My guess: often the particular people responding also have a protocol to follow, upheld by a further authority. For instance, perhaps the university police are required by protocol to keep you out of the building, and they too do not wish to cause some fight with their superiors. But at some point, didn’t there have to be an unpressured pressurer? A person who made a cautious choice not out of obedience? Probably, but writing a cautious policy for someone else, from a distance, long before a possible emergency, doesn’t much indicate that the author is shitting themselves about a possible fire, so they are probably totally free from this dynamic.

(If true, this seems like an observation we can make use of: if you want cautious behavior in situations where people will be incentivised to underreact, make policies from a distance, and or have them made by people who have no reason for fear.)

I feel like this one is actually a big part of why people leave buildings in response to fire alarms. (e.g. when I imagine less authority-imbued settings, I imagine the response being more lax). So when we say there is no fire alarm for AI, are we saying that there is no authority willing to get mad at us if we don’t panic at this somewhat arbitrary time?

One other nice thing to note about this model. For any problem, many levels of caution are possible: if an alarm causes everyone to think it is reasonable to ‘go and take a look’ but your own judgment is that the situation has reached ‘jump out of the window’ level, then you are probably still fairly oppressed by fear shame. Similarly, even if a foreign nation attacks an ally, and everyone says in unison, ‘wow, I guess it’s come to this, the time to act is now’, there will probably be people who think that it’s time to flee overseas or to bring out the nukes, and others who think it’s time to have a serious discussion with someone, and judgments will be flying. So for many problems, it seems particularly hard to imagine a piece of evidence that leads to total agreement on the reasonable course of action. The authority model deals with this because authority doesn’t mess around with being reasonable—it just cuts to the chase and tells you what to do.

By norms?

A different version of being ‘supposed to leave’ is that it is the norm, or what a cooperative person does. This seems similar in that it gives you reason to go outside, perhaps to the point of obligation, which is either strong enough to compel you outside even if you were still embarrassed, or anyway not related to whether you are fearful, and so unlikely to embarrass you. It still leaves the question of how a fire alarm came to have this power over what people are supposed to do.

By commitment?

Instead of having a distant authority compelling you to go outside, my guess is that you can in some situations get a similar effect by committing yourself at an earlier time where it wouldn’t have indicated fear. For instance, if you say, ‘I’m not too worried about this smoke, but if the fire alarm goes off, I’ll go outside’, then you have more reason to leave when the fire alarm does go off, while probably indicating less total fear. I doubt that this is a big way that fire alarms work, but it seems like a way people think about things like AI risk, especially if they fear psychologically responding to a gradual escalation of danger in the way that a boiling frog of myth does. They build an ‘alarm’, which sends them outside because they decided in the past that that would be the trigger.

By inflicting pain?

In my recollection, any kind of fire alarm situation probably involves an unbearably ear-splitting sound, and thus needs to be dealt with even if there is zero chance of fire. If leaving the building and letting someone else deal with it is available, it is an appealing choice. This mechanism is another form of ‘alternate motivation’, and I think is actually a lot like the authority one. The cost is arranged by someone elsewhere, in the past, who is free to worry on your behalf in such situations without shame; quite possibly the same authority. The added cost makes it easy to leave without looking scared, because now there is good incentive for even the least scared to leave, as long as they don’t like piercing shrieks (if you wanted to go really hard on signaling nonchalance, I think you could do so by just hanging out in the noise, but that end of the signaling spectrum seems like a separate issue).

My guess is that this plays some role, speaking as a person who once fled an Oxford dorm enough times in quick succession to be fairly unconcerned by fire by the last, but who still feels some of the ungodly horror of that sound upon recollection.

By alerting you to unseen fire?

Even if some of these stories seem plausible at times, I find it hard to believe that they are the main thing going on with fire alarms. My own guess is that actually fire alarms really do mostly help by alerting people who haven’t received much evidence of fire yet, e.g. because they are asleep. I’m not sure why Eliezer thinks this isn’t so. (For instance, look up ‘fire alarm saved my life’ or ‘I heard the fire alarm’ and you get stories about people being woken up in the middle of the night or sometimes alerted from elsewhere in the building and zero stories about anything other than that, as far as I can tell on brief perusal. I admit though that ‘my friends and I were sitting there watching the smoke in a kind of nonchalant stupor and then the fire alarm released us from our manly paralysis’ is not the most tellable story.)

I admit that the evidence is more confusing though – for instance, my recollection from a recent perusal of fire data is that people who die in fires (with or without fire alarms) are mostly not asleep. And actually the situation in general seemed pretty confusing, for instance, if I recall correctly, the most likely cause of a fatal fire appeared to be cigarette smoking, and the most likely time for it was the early afternoon. And while, ‘conscious person smoking cigarette at 1pm sets their room on fire and fails to escape’ sounds possible, I wouldn’t have pinned it as a central case. Some data also seemed to contradict, and I can’t seem to find most of it again now at all though, so I wouldn’t put much stock in any of this, except to note confusion.

My guess is still that this is a pretty big part of how fire alarms help, based on priors and not that much contrary evidence.

In sum: not much fire alarm for fires

My guess is that fire alarms do a decent mixture of many things here – sometimes they provide straightforward evidence of fires, sometimes they wake people up, sometimes they compel people outside through application of authority or unbearable noise, sometimes they probably even make it less embarrassing to react to other fire evidence, either via creating common-knowledge or just via being an impersonal standard that one can refer to.

So perhaps Eliezer’s ‘creating common knowledge of risk and so overcoming fear shame’ mechanism is part of it. But even if so, I don’t think it’s as much of a distinct thing. Like, there are various elements here that are helpful for combatting fear shame—evidence about the risk, impersonal evidence, a threshold in the situation already deemed concerning in the past, common knowledge. But there’s not much reason or need for them to come together in a single revolutionary event. And incremental versions of these things also help—e.g. A few people thinking it’s more likely that a concern is valid, or common knowledge of some compelling evidence among five people, or someone making a throwaway argument for concern, or evidence that some other people think the situation is worse without any change in the situation itself.

So—I think fire alarms can help people escape fires in various ways, some of which probably work via relieving paralysis from fear shame, and some of which probably relate to Eliezer’s ‘fire alarm’ concept, though I doubt that these are well thought of as a distinct thing.

And on the whole these mechanisms are a lot more amenable to partialness and incremental effects than suggested by the image of a single erupting siren pouring a company into a parking lot. I want to put fire alarms back there with many other observations, like hearing a loud bang, or smelling smoke: ambiguous and context dependent and open to interpretation that might seem laughable if it is too risk-averse. In the absence of authority to push you outside, probably people deal with these things by judging them, looking to others, discussing, judging more, iterating. Fire alarms are perhaps particularly as a form of evidence, but I’m not sure they are a separate category of thing.

If this is what fire alarms are, we often either do or could have them for AGI. We have evolving evidence. We have relatively person-independent evidence about the situation. We have evidence that it isn’t embarrassing to act. We have plenty of alternate face-saving reasons to act concernedly. We have other people who have already staked their own reputation on AGI being a problem. All of these things we could have better. Is it important whether we have a particular moment when everyone is freed of fear shame?

Is there a fire alarm for other risks?

That was all about how fire alarms work for fires. What about non-fire risks? Do they have fire alarms?

Outside of the lab, we can observe that humans have often become concerned about things before they were obviously going to happen or cause any problem. Do these involve ‘fire alarms’? It’s hard for me to think of examples of situations where something was so clear that everyone was immediately compelled to act on caution, without risk of embarrassment, but on the other hand thinking of examples is not my forte (asking myself now to think of examples of things I ate for breakfast last week, I can think of maybe one).

Here are some cases I know something about, where I don’t know of particular ‘fire alarms’, and yet it seems that caution has been abundant:

- Climate change: my guess is that there are many things that different people would call ‘fire alarms’, which is to say, thresholds of evidence by which they think everyone should be appalled and do something. Among things literally referred to as fire alarms, according to Google, are the Californian fires and the words of Greta Thunberg and scientists. Climate change hasn’t become a universally acknowledged good thing to be worried about, though it has become a universally-leftist required thing to be worried about, so if some particular event prompted that, that might be a lot like a fire alarm, but I don’t know of one.

- Ozone hole: on a quick Wikipedia perusal, the closest thing to a fire alarm seems to be that “in 1976 the United States National Academy of Sciences released a report concluding that the ozone depletion hypothesis was strongly supported by the scientific evidence” which seems to have caused a bout of national CFC bannings. But this was presumably prompted by smaller groups of people already being concerned and investigating. This seems more like ‘one person smells smoke and goes out looking for fire, and they find one and come back to report and then several of their friends also get worried’.

- Recombinant DNA: my understanding is that the Asilomar conference occurred after an escalation of concern beginning with a small number of people being worried about some experiments, with opposition from other scientists until the end.

- Covid: this seems to have involved waves of escalating and de-escalating average concern with very high variance in individual concern and action in which purportedly some people have continued to favor more incaution to their graves, and others have seemingly died of caution. I don’t know if there has ever been near universal agreement on anything, and there has been ample judgement in both directions about degrees of preferred caution.

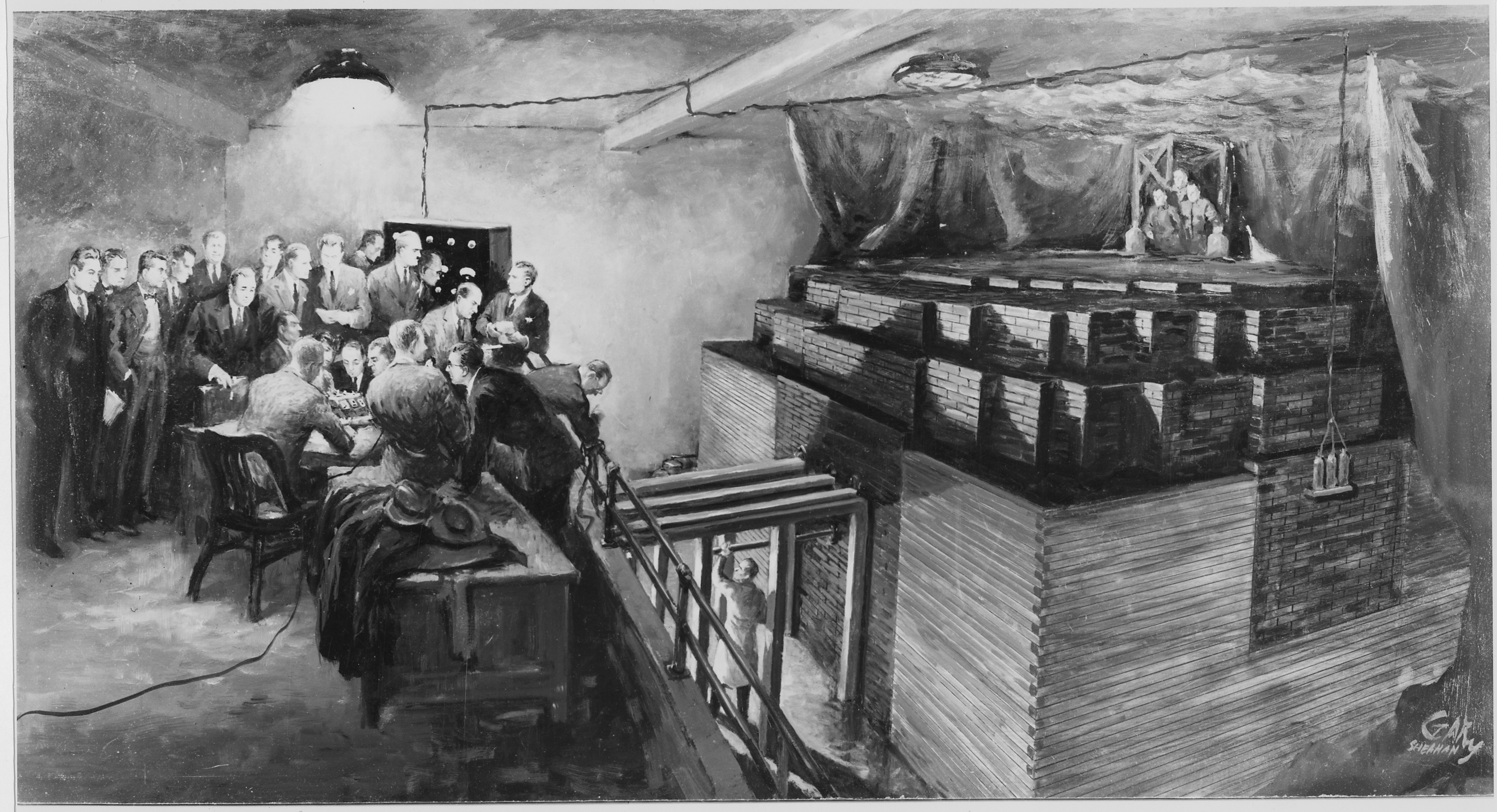

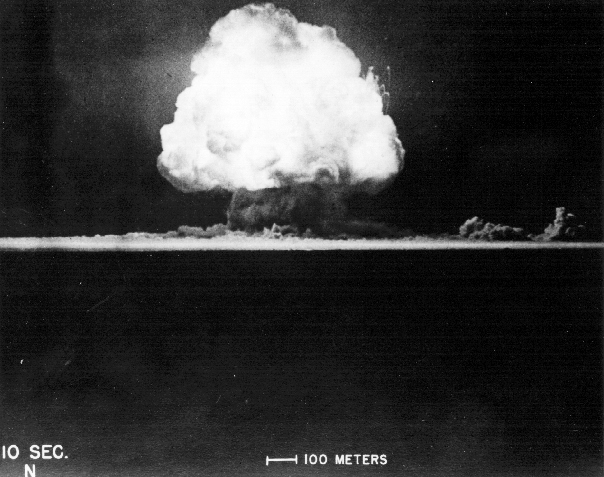

- Nuclear weapons: I don’t know enough about this. It seems like there was a fairly natural moment for everyone in the world to take the risk seriously together, which was the 6th of August 1945 bombing of Hiroshima. But if it was a fire alarm, it’s not clear what evacuating looks like. Stopping being at war with the US seems like a natural candidate, but three days later Japan hadn’t surrendered and the US bombed Nagasaki, which suggests Hiroshima was taken as less of a clear ‘evacuation time’. But I don’t know the details, and for instance, maybe surrendering isn’t straightforwardly analogous to evacuating.

- AI: It seems like there has been nothing like a ‘fire alarm’ for this, and yet for instance most random ML authors alike agree that there is a serious risk.10

My tentative impression is that history has plenty of concerns built on ambiguous evidence. In fact looking around, it seems like the world is full of people with concerns that are not only not shared by that many others, but also harshly judged. Many of which seem so patently unsupported by clinching evidence that it seems to me ‘rational socially-processed caution dampened by fear shame’ can’t be the main thing going on. I’ll get more into this later.

Summary: there are no ‘fire alarms’ for anything, and it’s fine (kind of)

In sum, it seems to me there is no ‘fire alarm’ for AGI, but also not really a fire alarm for fires, or for anything else. People really are stymied in responding to risks by fear of judgment. Many things can improve this, including things that fire alarms have. These things don’t have to be all or nothing, or bundled together, and there is plenty of hope of having many of them for AGI, if we don’t already.

So upon noting that there will be no fire alarm for AGI, if your best guess previously was that you should do nothing about AGI, I don’t think you should jump into action, assuming that you will be ever blind to a true signal. You should try to read the signals around you, looking out for these biases toward incaution.

But also: fire alarms are built

I think it’s interesting to notice how much fire alarms are about social infrastructure. Reading Eliezer’s post, I got the impression of the kind of ‘fire alarm’ that was missing as a clear and incontrovertible feature of the environment. For instance, an AI development that would leave everyone clear that there was danger, while still being early enough to respond. But the authority and pain infliction mechanisms are just about someone having created a trigger-action plan for you, and aggressive incentives for you to follow it, ahead of time. Even the common knowledge mechanisms work through humans having previously created the concept of a ‘fire alarm’ and everyone somehow knowing that it means you go outside. If fire alarms were instead a kind of organic object that we had discovered, with the kind of sensitivity to real fires that fire alarms have, I don’t even think that we’d run outside so fast. (I’m not actually even sure we would think of them as responding to fire—or like, maybe it would be rumored or known to fire alarm aficionados?)

Developments are basically always worrying for some people and not for others – so it seems hard for anything like common knowledge to come from a particular development. If you want something like universal common knowledge that such-and-such is non-embarrassing now to think, you are more likely to get it with a change in the social situation. E.g. “Steven Hawking now says AI is a problem” is arguably more like a fire alarm in this regard than AlphaGo—it is socially constructed, and involves someone else taking responsibility for the judgment of danger.

Even the components of fire alarm efficacy that are about conveying evidence of fire—to a person who hadn’t seen smoke, or understood it, or who was elsewhere, or asleep—are not naturally occurring. We built a system to respond to a particular subtle amount of smoke with a blaring alarm. The fact that there isn’t something like that for AI is appears to be because we haven’t built one. (New EA project proposal? Set up alarm system so that when we get to GPT-7 piercing alarms blare from all buildings until it’s out and responsible authorities have checked that the situation is safe.)

II. Fear shame and getting groupstruck

I think a better takeaway from all this research on people uncomfortably hanging out in smoke filled rooms is the fear shame hypothesis:

Shame about being afraid is a strong suppressor of caution.

Which is also to say:

your relaxed attitude to X is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame, for most X

(To be more concrete and help you to try out this hypothesis, without intending to sway you either way:

- Your relaxed attitude to soil loss is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame

- Your relaxed attitude to risk from nanotechnology is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame

- Your relaxed attitude to risk from chemicals in paint is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame

- Your relaxed attitude to Democratic elites drinking the blood of children is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame

- Your relaxed attitude to spiders is partly due to uncalibrated avoidance of social shame)

How is information about risk processed in groups in practice by default?

Here it seems helpful to have a model of what is going on when a group responds to something like smoke, minus whatever dysfunction or bias comes from being scared of looking like a pansy.

The standard fire-alarm-free group escape

In my experience, if there is some analog of smoke appearing in the room, people don’t just wait in some weird tragedy of the commons until they drop dead. There is an escalation of concern. One person might say ‘hey, can you smell something?’ in a tone that suggests that they are pretty uncertain, and just kind of curious, and definitely not concerned. Then another person sniffs the air and says in a slightly more niggled tone, ‘yeah, actually – is it smoke?’. And then someone frowns as if this is all puzzling but still not that concerning, and gets up to take a look. And then if anyone is more concerned, they can chime in with ‘oh, I think there’s a lot of dry grass in that room too, I hope the spark generator hasn’t lit some of it’, or something.

I’m not sure whether this is an incredibly good way to process information together about a possible fire, but it seems close to a pretty reasonable and natural method: each person expresses their level of concern, everyone updates, still-concerned people go and gather new information and update on that, this all repeats until the group converges on concern or non-concern. I think of this as the default method.

It seems to me that what people actually do is this plus some adjustments from e.g. people expecting social repercussions if they express a different view to others, and people not wanting to look afraid. Thus instead we see the early reports of concern downplayed emotionally, for instance joked about, both allowing the reporter to not look scared, and also making it a less clear bid for agreement, so allowing the other person to respond with inaction, e.g. by laughing at the joke and dropping the conversation. I’m less clear on what I see exactly that makes me think there is also a pull toward agreeing, or that saying a thing is like making a bid for others to agree, and disagreeing is a potentially slightly costly social move, except for my intuitive sense of such situations.

It’s not obvious to me that crippling embarrassment is a bias on top of this kind of arrangement, rather than a functional part of it. If each person has a different intrinsic level of fear, embarrassment might be genuinely aligning people who would be too trigger-happy with their costly measures of caution. And it’s not obvious to me that embarrassment doesn’t also affect people who are unusually incautious. (Before trying to resolve embarrassment in other ways, it seems good to check whether it is a sign that you are doing something embarrassing.)

Two examples of groups observing ambiguous warning signs without fire alarms in the wild, from the time when Eliezer’s post came out and I meant to write this:

- At about 3am my then-boyfriend woke up and came and poked his head around my door and asked whether I could smell smoke. I said that I could, and that I had already checked the house, and that people on Twitter could also smell it, so it was probably something large and far away burning (as it happened, I think Napa or Sonoma). He went to bed, and I checked the house one more time, to be sure and/or crazy.

- I was standing in a central square in a foreign city with a group of colleagues. There was a very loud bang, that sounded like it was a stupendously loud bang some short distance away. People in the group glanced around and remarked on it, and then joked about it, and then moved to other topics. I remained worried, and surreptitiously investigated on my phone, and messaged a friend with better research resources at hand.

I think Case 2 nicely shows the posited fear shame (though both cases suggest a lack of it with close friends). But in both cases, I think you see the social escalation of concern thing. In the first case my boyfriend actually sought me out to casually ask about smoke, which is very surprising on a model where the main effect of company is to cause crippling humiliation. Then it didn’t get further because I had evidence to reassure him. In the second case, you might say that the group was ignoring the explosion-like-thing out of embarrassment. But I hypothesize that they were actually doing a ratcheting thing that could have led to group fear, that quickly went downward. They remarked casually on the thing, and jokingly wondered about bombs and such. And I posit that when such jokes were met with more joking instead of more serious bombs discussion, the ones who had been more concerned became less so.

The smoke experiment video also suggests that this kind of behavior is what people expect to do: the first woman says, ‘I was looking for some sort of reaction from someone else. Even just the slightest little thing, that they’d recognize that there was something, you know, going on here. For me to kind of, react on that and then do something about it. I kind of needed prodding.”

I think this model also describes metaphorical smoke. In the absence of very clear signs of when to act, people indeed seem embarrassed to seem too concerned. For instance, they are sometimes falling over themselves to be distanced from those overoptimistic AI-predictors everyone has heard about. But my guess is that they avoid embarrassment not by sitting in silence until they drown in metaphorical smoke, but with a social back and forth maneuver—pushing the conversation toward more concern each time as long as they are concerned—that ultimately coordinates larger groups of people to act at some point, or not. People who don’t want to look like feverish techno-optimists are still comfortable wondering aloud whether some of this new image recognition stuff might be put to ill-use. And if that goes over well, next time they can be a little more alarmist. There is an ocean of ongoing conversation, in which people can lean a little this way and that, and notice how the current is moving around them. And in general—before considering possible additional biases—it isn’t clear to me that this coordination makes things worse than the hypothetical embarrassment-free world of early and late unilateral actions.11

In sum I think the basic thing people do when responding to risks in a group is to cautiously and conformingly trade impressions of the level of danger, leading to escalating concern if a real problem is arising.

Sides

A notable problem with this whole story so far is that people love being concerned. Or at least, they are often concerned in spite of a shocking dearth of evidential support, and are not shy about sharing their concerns.

I think one thing going on is that people mostly care about criticism coming from within their own communities, and that for some reason concerns often become markers of political alignment. So if for instance the idea that there may be too many frogs appearing is a recognized yellow side fear, then if you were to express that fear with great terror, the whole yellow side would support you, and you would only hear mocking from the heinous green side. If you are a politically involved yellow supporter, this is a fine state of affairs, so you have no reason to underplay your concern.

This complicates our pluralistic inaction story so much that I’m inclined to just write it off as a different kind of situation for now: half the people are still embarrassed to overtly express a particular fear, but for new reasons, and the other half are actively embarrassed to not express it, or to express it too quietly. Plus everyone is actively avoiding conforming with half of the people.

I think this kind of dynamic is notably at play with climate change case, and weirdly-to-me also with covid. My guess is that it’s pretty common, at least to a small degree, and often not aligned with the major political sides. Even if there are just sides to do with the issue itself, all you need for this is that people feel a combination of good enough about the support of their side and dismissive enough of the other side’s laughter to voice their fears.

In fact I wonder if this is not a separate issue, and actually a kind of natural outcome of the initial smelling of smoke situation, in a large enough crowd (e.g. society). If one person for some reason is worried enough to actually break the silence and flee the building, then they have sort of bet their reputation on there being a fire, and while others are judging that person, they are also updating a) that there is more likely to be a fire, and b) that the group is making similar updates, and so it is less embarrassing to leave. So one person’s leaving makes it easier for each of the remaining people to leave12. Which might push someone else over the edge into leaving, which makes it even easier to leave for the next person. If you have a whole slew of people leaving, but not everyone, and the fire takes a really long time to resolve, then (this isn’t game theory but my own psychological speculations) I can imagine the people waiting in the parking lot and the people sticking it out inside developing senses of resentment and judgment toward the people in the other situation, and camaraderie toward those who went their way.

You can actually see a bit of something like this in the video of the Asch conformity experiments—when another actor says the true answer, the subject says it too and then is comradely with the actor:

My guess is that in many cases even one good comrade is enough to make a big difference. Like, if you are in a room with smoke, and one other person is willing to escalate concern with you, it’s not hard to imagine the two of you reporting it together, while having mild disdain for the sheeple who would burn.

So I wonder if groupishness is actually part of how escalation normally works. Like, you start out with a brave first person, and then it is easier to join them, and a second person comes, and you form a teensy group which grows (as discussed above) but also somewhere in there becomes groupish in the sense of its members being buoyed enough by their comrades’ support and dismissive enough of the other people that the concerned group are getting net positive social feedback for their concern. And then the concerned group grows more easily by there being two groups you can be in as a conformist. And by both groups getting associated with other known groups and stereotypes, so that being in the fearful group signals different things about a person than fearfulness. On this model, if there is a fire, this gets responded to by people gradually changing into the ‘building is on fire’ group, or newcomers joining it, and eventually that group becoming the only well respected one, hopefully in time to go outside.

In sum, we see a lot of apparently uncalled for and widely advertised fearfulness in society, which is at odds with a basic story of fear being shameful. My guess is that this is a common later part of the dynamic which might begin as in the experiments, with everyone having trouble being the first responder.

Note that this would mean the basic fire alarm situation is less of a good model of real world problems of the kind we might blog about, where by the time you are calling for people to act in spite of their reluctance to look afraid, you might already be the leader of the going outside movement which they could join in relatively conformist ease, perhaps more at the expense of seeming like a member of one kind of group over another than straightforwardly looking fearful.

Is the fear shame hypothesis correct?

I think the support of this thesis from the present research is actually not clear. Darley and Latané’s experiment tells us that people in groups react less to a fire alarm than individuals. But is the difference about hiding fear? Does it reveal a bias? Is it the individuals who are biased, and not the group?

Is there a bias at all?

That groups and individuals behave differently doesn’t mean that one of the two is wrong. Perhaps if you have three sources of evidence on whether smoke is alarming, and they are overall pointing at ‘doubtful’, then you shouldn’t do anything, whereas if you only have one and it is also pointing at ‘doubtful’, you should often gather more evidence.

It could also be that groups are generally more correct due to having more data, and whether they are more or less concerned than individuals actually varies based on the riskiness of the situation. Since these kinds of experiments are never actually risky, our ability to infer that a group is under-reacting relies on the participants being successfully misled about the degree of risk. But maybe they are only a bit misled, and things would look very different if we watched groups and individuals in real situations of danger. My guess is that society acts much more on AI risk and climate change than the average of individuals’ behavior, if the individuals were isolated from others with respect to that topic somehow.

Some evidence against a bias is that groups don’t seem to be consistently less concerned about risk than individuals, in the wild. For instance, ‘panics’ are a thing I often hear that it would be bad to start.

Also, a poll of whoever sees such things on my Twitter suggests that while rarer, a decent fraction of people feel social pressure toward being cautious more often than the reverse:

Facing a risk, do you more often find yourself A) inclined to take a precaution but fearful of being judged for it, or B) inclined to take no precaution but fearful of being judged for that?

— Katja Grace (@KatjaGrace) September 8, 2021

Are groups not scared enough or are individuals too scared?

Even if there is a systematic bias between groups and individuals, it isn’t obvious that groups are the ones erring. They appear to be in these fire alarm cases, but a) given that they are in fact correct, it seems like they should get some benefit of the doubt, and b) these are a pretty narrow set of cases.

An alternate theory here would be that solitary people are often poorly equipped to deal rationally with risks, and many tend to freak out and check lots of things they shouldn’t check, but this is kept in check in a group setting by some combination of reassurance of other people, shame about freaking out over nothing, and conformity. I don’t really know why this would be the situation, but I think it has some empirical plausibility, and it wouldn’t be that surprising to me if humans were better honed for dealing with risks in groups than as individuals. (D&L suggest a hypothesis like this, but think it isn’t this, because the group situation seemed to alter participants likelihood of interpreting the smoke as fire, rather than their reported ability to withstand the danger. I’m less sure that inclination to be fearless wouldn’t cause people to interpret smoke differently.)

One might think a reason against this hypothesis is that this shame phenomenon seems to be a bias in the system, so probably the set who are moved by it (people in groups) are the ones who are biased. But you might argue that shame is maybe a pretty functional response to doing something wrong, and so perhaps you should assume that the people feeling shame are the ones who would otherwise be doing something wrong.

Is it because they want to hide their fear?

In an earlier study, D&L observed participants react less to an emergency that other participants could see, even when the others couldn’t see how they responded to it.

D&L infer that there are probably multiple different things going on. Which might be true, but it does pain me to need two different theories to explain two very similar datapoints.

Another interesting fact about these experiments is that the participants don’t introspectively think they interpret the smoke as fire, and want to escape, but are concerned about looking bad. If you ask them, apparently they say that they just didn’t think it was fire:

“Subjects who had not reported the smoke also were unsure about exactly what it was, but they uniformly said that they had rejected the idea that it was a fire. Instead, they hit upon an astonishing variety of alternative explanations, all sharing the common characteristic of interpreting the smoke as a nondangerous event. Many thought the smoke was either steam or air-conditioning vapors, several thought it was smog, purposely introduced to simulate an urban environment, and two (from different groups) actually suggested that the smoke was a “truth gas” filtered into the room to induce them to answer the questionnaire accurately. (Surprisingly, they were not disturbed by this conviction.) Predictably, some decided that “it must be some sort of experiment” and stoicly endured the discomfort of the room rather than overreact.

Despite the obvious and powerful report inhibiting effect of other bystanders, subjects almost invariably claimed that they had paid little or no attention to the reactions of the other people in the room. Although the presence of other people actually had a strong and pervasive effect on the subjects’ reactions, they were either unaware of this or unwilling to admit it.”

I don’t take this as strong evidence against the theory, because this seems like what it might look like for a human to see ambiguous evidence and at some level want to avoid seeming scared. Plus if you look at the video of this experiment being rerun, the people in groups not acting do not look uniformly relaxed.

For me a big plus in the theory of fear shame is that it introspectively seems like a thing. I’m unusually disposed toward caution in many circumstances, and also an analytic approach that both doesn’t match other people’s intuitive assessments of risk always, and isn’t very moved by observing this. And I do feel the shame of it. This year has allowed particular observation of this: it is just embarrassing, for me at least, to wear a heavy duty P100 respirator in a context where other people are not. Even if the non-social costs of wearing a better mask are basically zero in a situation (e.g. I don’t need to talk, I’m kind of enjoying not having my face visible), it’s like there is an invisible demand rising from the world, ‘why are you wearing such a serious mask? Is it that you think this is dangerous?’ (‘Only a little bit dangerous, please, I’m just like you, it’s just that on net I don’t really mind wearing the bigger mask, and it is somewhat safer, so why not?’13)

But on further consideration, I think introspection doesn’t support this theory. Because a much broader set of things than fear seem to produce a similar dynamic to seeing smoke in a group, or to in other cases where I feel unable to take the precautions I would want because of being observed.

Here are some actions that feel relatedly difficult to me—probably either because the outward behavior seem similar or because I expect a similar internal experience—but where the threat of seeming too fearful in particular isn’t the issue:

- Wearing a weird outfit in public, like a cape (this feels fairly similar to wearing a heavy duty mask in public, e.g. I’m inclined not to though there are no obvious consequences, and if I do, my brain becomes obsessed with justifying itself)

- Wearing no mask in a context where others have masks (my friend says this feels similarly hard to wearing an overly large mask to him)

- Getting up and leaving a room of people doing a questionnaire if there appeared to be hundred dollar bills falling from the sky outside the window (I expect this to feel somewhat similar to seeing smoke)

- Answering a question differently from everyone else in front of the room, as in the classic Asch conformity experiments (I expect this to feel a bit like seeing smoke, and the behavior looks fairly similar: a person is offered a choice in front of a group who all seem to be taking the apparently worse option)

- Being shown a good-seeming offer with a group of people, e.g. an ad offering a large discount on a cool object if you call a number now (I would find it hard to step out and phone the number, unless I did it surreptitiously)

- Being in a large group heading to a Japanese restaurant, and realizing that given everyone’s preferences, an Italian restaurant would be better (I think this would feel a bit like seeing smoke in the room, except that the smoke wasn’t even going to kill you)

- Sitting alone at a party, in a way that suggests readiness to talk, e.g. not looking at phone or performing solitary thoughtfulness (this makes me want to justify myself, like when wearing a big mask, and is very hard to do, maybe like standing up and leaving upon seeing smoke)

- Leaving a large room where it would be correct to say goodbye to people, but there are so many of them, and they are organized such that if you say goodbye to any particular person, many others will be watching, and to say goodbye to everyone at once you will have to shout and also interrupt people, and also may not succeed in actually getting everyone’s attention, or may get it too loudly and seem weird (this has an, ‘there’s an obviously correct move here, and I somehow can’t do it because of the people’ feeling, which I imagine is similar to the smoke)

- If a class was organizing into groups in a particular way, and you could see a clearly better way of doing it, telling the class this

- Shouting a response to someone calls out a question to a crowd

- Walking forward and investigating whether a person is breathing, when they have collapsed but there is a crowd around them and you don’t know if anyone has done anything

- Getting up to help someone who has fallen into the subway gap when lots of people can see the situation

- Stepping in to stop a public domestic violence situation

- Getting up to tell a teacher when a group of other students are sticking needles into people’s legs (this happened to me in high school, and I remember it because I was so paralyzed for probably tens of minutes while also being so horrified that I was paralyzed)

- Asking strangers to use their credit card to make an important phone call on the weird public phones on a ship (this also happened to me, and I was also mysteriously crippled and horrified)

- Criticizing someone’s bad behavior when others will see (my friend says he would feel more game to do this alone, e.g. if he saw someone catcalling a woman rudely)

- Correcting a professor if they have an equation wrong on the board, when it’s going to need to be corrected for the lesson to proceed sensically, and many people can see the issue

- Doing anything in a very large room with about six people scattered around quietly, such that your actions are visible and salient to everyone and any noise or sudden motion you make will get attention

- Helping to clean up a kitchen with a group of acquaintances, e.g. at a retreat, where you are missing information for most of the tasks (e.g. where do chopping boards live, do things need to be rinsed off for this dishwasher, what is this round brown object, did it all start out this dirty?)

- Doing mildly unusual queueing behavior for the good of all. For instance, standing in a long airport queue, often everyone would be better off if a gap were allowed to build at the front of the queue and then everyone walked forward a longer distance at once, instead of everyone edging forward a foot at a time. This is because often people set down their objects and read on their phones or something while waiting, so it is nicer to pick everything up and walk forward five meters every few minutes than it is to pick everything up and walk forward half a meter every twenty seconds. Anyone in the queue can start this, where they are standing, by just not walking forward when the person in front of them does. This is extremely hard to do, in my experience.

- Asking or answering questions in a big classroom. I think professors have trouble getting people to do this, even when students have questions and answers.

- Not putting money in a hat after those around you have

- Interacting with a child with many adults vaguely watching

- Taking action on the temperature being very high as a student in a classroom

- Cheering for something you liked when others aren’t

- Getting up and dancing when nobody else is

- Walking across the room in a weird way, in most situations

- Getting up and leaving if you are watching something that you really aren’t liking with a group of friends

Salient alternate explanations:

- Signaling everything: people are just often encumbered any time people are looking at them, and might infer anything bad about them from their behavior. It’s true that they don’t want to seem too scared, but they also don’t want to seem too naively optimistic (e.g. believing that money is falling from above, or that they are being offered a good deal) or to not know about fashion (e.g. because wearing a cape), or to be wrong about how long different lines are (e.g. in the Asch experiments).

- Signaling weirdness: as in 1, but an especially bad way to look is ‘weird’, and it comes up whenever you do anything different from most other people, so generally cripples all unusual behavior.

- Conformity is good: people just really like doing what other people are doing.

- Non-conformity is costly: there are social consequences for nonconformity (2 is an example of this, but might not be the only one).

-

Non-conformity is a bid for being followed: if you are with others, it is good form to collaboratively decide what to do14. Thus if you make a move to do something other than what the group is doing, it is implicitly a bid for others to follow, unless you somehow disclaim it as not that. According to intuitive social rules, others should follow iff you have sufficient status, so it is also a bid to be considered to have status. This bid is immediately resolved in a common knowledge way by the group’s decision about whether to follow you. If you just want to leave the room and not make a bid to be considered high status at the same time—e.g. because that would be wildly socially inappropriate given your actual status—then you can feel paralyzed by the lack of good options.

This model fits my intuitions about why it is hard to leave. If I imagine seeing the smoke, and wanting to leave, what seems hard? Well, am I just going to stand up and quietly walk out of the room? That feels weird, if the group seems ‘together’ – like, shouldn’t I say something to them? Ok, but what? ‘I think we should go outside’? ‘I’m going outside’? These are starting to sound like bids for the group agreeing with me. Plus if I say something like this quietly, it still feels weird, because I didn’t address the group. And if I address the group, it feels a lot like some kind of status-relevant bid. And when I anticipate doing any of these, and then nobody following me, that feels like the painful thing. (I guess at least I’m soon outside and away from them, and I can always move to a new city.)

On this theory, if you could find a way to avoid your actions seeming like a bid for others to leave, things would be fine. For instance, if you said, ‘I’m just going to go outside because I’m an unreasonably cautious person’, on this theory it would improve the situation, whereas on the fear shame hypothesis, it would make it worse. My own intuition is that it improves the situation. - Non-conformity is conflict: not doing what others are doing is like claiming that they are wrong, which is like asking for a fight, which is a socially scary move.

- Scene-aversion: people don’t like ‘making a scene’ or ‘making a fuss’. They don’t want to claim that there’s a fire, or phone 911, or say someone is bad, or attract attention, or make someone nearby angry. I’m not sure what a scene is. Perhaps a person has made one if they are considered responsible for something that is ‘a big deal’. Or if someone else would be right in saying, ‘hey everyone, Alice is making a bid for this thing to be a big deal’

These are not very perfect or explanatory or obviously different, but I won’t dive deeper right now. Instead, I’ll say a person is ‘groupstruck’15 if they are in any way encumbered by the observation of others.

My own sense is that a mixture of these flavors of groupstruckness happen in different circumstances, and that one could get a better sense of which and when if one put more thought into it than I’m about to.

A big question that all this bears on is whether there is a systematic bias away from concern about risks, in public e.g. in public discourse. If there is—if people are constantly trying to look less afraid than they are—then it seems like an important issue. If not, then we should focus on other things, for instance perhaps a lurking systematic bias toward inaction.

My own guess is that the larger forces we see here are not about fear in particular, and after the first person ‘sounds the alarm’ as it were, and some people are making their way outside, the forces for and against the side of higher caution are more messy and not well thought of as a bias against caution (e.g. worrying about corporate profits or insufficient open source software or great power war mostly makes you seem like one kind of person or another, rather than especially fearful). My guess is that these dynamics are better thought of as opposing a wide range of attention-attracting nonconformism. That said, my guess is that overall there are somewhat stronger pressures against fear than in favor of it, and that in many particular instances, there is a clear bias against caution, so it isn’t crazy to think of ‘fear shame’ as a thing, if a less ubiquitous thing, and maybe not a very natural category.

III. Getting un-groupstruck

How can fear shame and being groupstruck be overcome? How are things like this overcome in practice, if they ever are? How should we overcome them?

Some ideas that might work if some of the above is true, many inspired by aspects of fire alarms:

- A person or object to go first, and receive the social consequences of nonconformity

For instance, a person whose concern is not discouraged by social censure, or a fire alarm. There is no particular need for this to be a one-off event. If Alice is just continually a bit more worried than others about soil loss, this seems like it makes it easier for others to be more concerned than they would have been. Though my guess is that often the difference between zero and one people acting on a concern is especially helpful. In the case of AI risk, this might just mean worrying in public more about AI risk. - Demonstrate your non-judgmentalness

Others are probably afraid of you judging them often. To the extent that you aren’t also oppressed by fear of judgment from someone else, you can probably free others some by appearing less judgmental. - Other incentives to do the thing, producing plausible deniability

Cool parties to indicate your concern, prestigious associations about it… - Authorities enforcing caution

Where does the shame-absorbing magic of a real fire alarm come from, when it has it? From an authority such as building management, or your school, or the fire brigade, who you would have to fight to disobey. - ‘Fire wardens’