AI Impacts spoke with computer scientist Ernie Davis about his views of AI risk. With his permission, we have transcribed this interview.

Participants

- Ernest Davis – professor of computer science at the Courant Institute of Mathematical Science, New York University

- Robert Long – AI Impacts

Summary

We spoke over the phone with Ernie Davis on August 9, 2019. Some of the topics we covered were:

- What Davis considers to be the most urgent risks from AI

- Davis’s disagreements with Nick Bostrom, Eliezer Yudkowsky, and Stuart Russell

- The relationship between greater intelligence and greater power

- How difficult it is to design a system that can be turned off

- How difficult it would be to encode safe ethical principles in an AI system

- Davis’s evaluation of the likelihood that advanced, autonomous AI will be a major problem within the next two hundred years; and what evidence would change his mind

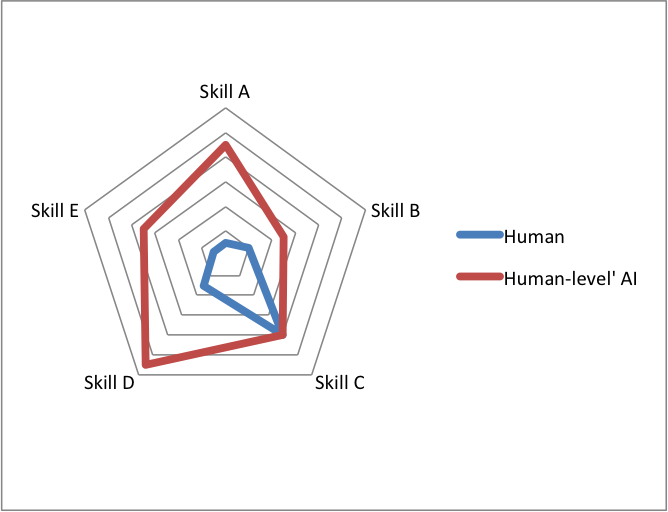

- Challenges and progress towards human-level AI

This transcript has been lightly edited for concision and clarity.

Transcript

Robert Long: You’re one of the few people, I think, who is an expert in AI, and is not necessarily embedded in the AI Safety community, but you have engaged substantially with arguments from that community. I’m thinking especially of your review of Superintelligence.1 2

I was hoping we could talk a little bit more about your views on AI safety work. There’s a particular proposition that we’re trying to get people’s opinions on. The question is: Is it valuable for people to be expending significant effort doing work that purports to reduce the risk from advanced artificial intelligence? I’ve read some of your work; I can guess some of your views. But I was wondering: what would you say is your answer to that question, whether this kind of work is valuable to do now?

Ernie Davis: Well, a number of parts to the answer. In terms of short term—and “short” being not very short—short term risks from computer technology generally, this is very low priority. The risks from cyber crime, cyber terrorism, somebody taking hold of the insecurity of the internet of things and so on—that in particular is one of my bugaboos—are, I think, an awful lot more urgent. So there’s urgency; I certainly don’t see that this is especially urgent work.

Now, some of the approaches are being taken to long term AI safety seem to me extremely far fetched. On the one hand the fears of people like Bostrom and Yudkowsky and to a lesser extent Stuart Russell—seem to me misdirected and the approaches they are proposing are also misdirected. I have a book with Gary Marcus which is coming out in September, and we have a chapter which is called ‘Trust’ which gives our opinions—which are pretty much convergent—at length. I can send you that chapter.

Robert Long: Yes, I’d certainly be interested in that.

Ernie Davis: So, the kinds of things that Russell is proposing—Russell also has a book coming out in October, he is developing ideas that he’s already published about: the way to have safe AI is to have them be unsure about what the human goals are.3 And Yudkowsky develops similar ideas in his work, engages with them, and tries to measure their success. This all seems to me too clever by half. And I don’t think it’s addressing what the real problems are going to be.

My feeling is that the problem of AIs doing the wrong thing is a very large one—you know, just by sheer inadvertence and incompetent design. And the solution there, more or less, is to design them well and build in safety features of the kinds that one has in engineering, one has throughout engineering. Whenever one is doing an engineering project, one builds in—one designs for failure. And one has to do that with AI as well. The danger of AI being abused by bad human actors is a very serious danger. And that has to be addressed politically, like all problems involving bad human actors.

And then there are directions in AI where I think it’s foolish to go. For instance it would be very foolish to build—it’s not currently technically feasible, but if it were, and it may at some point become technically feasible—to build robots that can reproduce themselves cheaply. And that’s foolish, but it’s foolish for exactly the same reason that you want to be careful about introducing new species. It’s why Australia got into trouble with the rabbits, namely: if you have a device that can reproduce itself and it has no predators, then it will reproduce itself and it gets to be a nuisance.

And that’s almost separate. A device doesn’t have to be superintelligent to do that, in fact superintelligence probably just makes that harder because a superintelligent device is harder to build; a self replicating device might be quite easy to build on the cheap. It won’t survive as well as a superintelligent one, but if it can reproduce itself fast enough that doesn’t matter. So that kind of thing, you want to avoid.

There’s a question which we almost entirely avoided in our book, which people always ask all the time, which is, at what point do machines become conscious. And my answer to that—I’m not necessarily speaking for Gary—my answer to that is that you want to avoid building machines which you have any reason to suspect are conscious. Because once they become conscious, they simply raise a whole collection of ethical issues like—”is it ethical turn them off?”, is the first one, and “what are your responsibilities toward the thing?”. And so you want to continue to have programs which, like current programs, one can think of purely as tools which we can use, which it is ethical to use as we choose.

So that’s a thing to be avoided, it seems to me, in AI research. And whether people are wise enough to avoid that, I don’t know. I would hope so. So in some ways I’m more conservative than a lot of people in the AI safety world—in the sense that they assume that self replicating robots will be a thing and that self-aware robots will be a thing and the object is to design them safely. My feeling is that research shouldn’t go there at all.

Robert Long: I’d just like to dig in on a few more of those claims in particular. I would just like to hear a little bit more about what you think the crux of your disagreement is with people like Yudkowsky and Russell and Bostrom. Maybe you can pick one because they all have different views. So, you said that you feel that their fears are far-fetched and that their approaches are far-fetched as well. Can you just say a little bit about more about why you think that? A few parts: what you think is the core fear or prediction that their work is predicated on, and why you don’t share that fear or prediction.

Ernie Davis: Both Bostrom very much, and Yudkowsky very much, and Russell to some extent, have this idea that if you’re smart enough you get to be God. And that just isn’t correct. The idea that a smart enough machine can do whatever it want—there’s a really good essay by Steve Pinker, by the way, have you seen it?4

Robert Long: I’ve heard of it but have not read it.

Ernie Davis: I’ll send you the link. A couple of good essays by Pinker, I think. So, it’s not the case that once superintelligence is reached, then times become messianic if they’re benevolent and dystopian if they’re not. They’re devices. They are limited in what they can do. And the other thing is that we are here first, and we should be able to design them in such a way that they’re safe. It is not really all that difficult to design an AI or a robot which you can turn off and which cannot block you from turning it off.

And it seems to me a mistake to believe otherwise. With two caveats. One is that, if you embed it in a situation where it’s very costly to turn off—it’s controlling the power grid and the power grid won’t work if you turn it off, then you’re in trouble. And secondly, if you have malicious actors who are deliberately designing, building devices which can’t be turned off. It’s not that it’s impossible to build an intelligent machine that is very dangerous.

But that doesn’t require superintelligence. That’s possible with very limited intelligence, and the more intelligent, to some extent, the harder it is. But again that’s a different problem. It doesn’t become a qualitatively different problem once the thing has exceeded some predefined level of intelligence.

Robert Long: You might be even more familiar with these arguments than I am—in fact I can’t really recite them off the top of my head—but I suppose Bostrom and Yudkowsky, and maybe Russell too, do talk about this at length. And I guess they’re they’re always like, Well, you might think you have thought of a good failsafe for ensuring these things won’t get un-turn-offable. But, so they say, you’re probably underestimating just how weird things can get once you have superintelligence.

I suppose maybe that’s precisely what you’re disagreeing with: maybe they’re overestimating how weird and difficult things get once things are above human level. Why do you think you and they have such different hunches, or intuitions, about how weird things can get?

Ernie Davis: I don’t know, I think they’re being unrealistic. If you take a 2019 genius and you put him into a Neolithic village, they can kill him no matter how intelligent he is, and how much he knows and so on.

Robert Long: I’ve been trying to trace the disagreements here and I think a lot of it does just maybe come down to people’s intuitions about what a very smart person can do if put in a situation where they are far smarter than other people. I think this actually comes up in someone who responded to your review. They claim, “I think if I went back to the time of the Romans I could probably accrue a lot of power just by knowing things that they did not know.”5

Ernie Davis: I missed that, or I forgot that or something.

Robert Long: Trying to locate the crux of the disagreement: one key disagreement is what the relationship is between greater intellectual capacity and greater physical power and control over the world. Does that seem safe to say, that that’s one thing you disagree with them about?

Ernie Davis: I think so, yes. That’s one point of disagreement. A second point of disagreement is the difficulty of—the point which we make in the book at some length is that, if you’re going to have an intelligence that’s in any way comparable to human, you’re going to have to build in common sense. It’s going to have to have a large degree of commonsense understanding. And once an AI has common sense it will realize that there’s no point in turning the world into paperclips, and that there’s no point in committing mass murder to go fetch the milk—Russell’s example—and so on. My feeling is that one can largely incorporate a moral sense, when it becomes necessary; you can incorporate moral rules into your robots.

And one of the people who criticized my Bostrom paper said, well, philosophers haven’t solved the problems of ethics in 2,000 years, how do you think we’re going to solve them? And my feeling is we don’t have to come up with the ultimate solution to ethical problems. You just have to make sure that they understand it to a degree that they don’t do spectacularly foolish and evil things. And that seems to me doable.

Another point of disagreement with Bostrom in particular, and I think also Yudkowsky, is that they have the idea that ethical senses evolve—which is certainly true—and that a superintelligence, if well-designed, can be designed in such a way that it will itself evolve toward a superior ethical sense. And that this is the thing to do. Bostrom goes into this at considerable length: somehow, give it guidance toward an ethical sense which is beyond anything that we currently understand. That seems to me not very doable, but it would be a really bad thing to do if we could do it, because this super ethics might decide that the best thing to do is to exterminate the human population. And in some super-ethical sense that might be true, but we don’t want it to happen. So the belief in the super ethics—I have no belief, I have no faith in the super ethics, and I have even less faith that there’s some way of designing an AI so that as it grows superintelligent it will achieve super ethics in a comfortable way. So this all seems to me pie in the sky.

Robert Long: So the key points of disagreement we have so far are the relationship between intelligence and power; and the second thing is, how hard is what we might call the safety problem. And it sounds like even if you became more worried about very powerful AIs, you think it would not require substantial research and effort and money (as some people think) to make them relatively safe?

Ernie Davis: Where I would put the effort in is into thinking about, from a legal regulatory perspective, what we want to do. That’s not an easy question.

The problem at the moment, the most urgent question, is the problem of fake news. We object to having bots spreading fake news. It’s not clear what the best way of preventing that is without infringing on free speech. So that’s a hard problem. And that is, I think, very well worth thinking about. But that’s of course a very different problem. The problems of security at the practical level—making sure that an adversary can’t take control of all the cars that are connected to the Internet and start using them as weapons—is, I think, a very pressing problem. But again that has nothing much to do with the AI safety projects that are underway.

Robert Long: Kind of a broad question—I was curious to hear what you make of the mainstream AI safety efforts that are now occurring. My rough sense is since your review and since Superintelligence, AI safety really gained respectability and now there are AI safety teams at places like DeepMind and OpenAI. And not only do they work on the near-term stuff which you talk about, but they are run by people who are very concerned about the long term. What do you make of that trend?

Ernie Davis: The thing is, I haven’t followed their work very closely, to tell you the truth. So I certainly don’t want to criticize it very specifically. There are smart and well-intentioned people on these teams, and I don’t doubt that a lot of what they’re doing is good work.

The work I’m most enthusiastic about in that direction is problems that are fairly near term. And also autonomous weapons is a pretty urgent problem, and requires political action. So the more that can be done about keeping those under control the better.

Robert Long: Do you think your views on what it will take before we ever get to human-level or more advanced AI, do you think that drives a lot of your opinions as well? For example, your own work on common sense and how hard of a problem that can be?6 7

Ernie Davis: Yeah sure, certainly it informs my views. It affects the question of urgency and it affects the question of what the actual problems are likely to be.

Robert Long: What would you say is your credence, your evaluation of the likelihood, that without significant additional effort, advanced AI poses a significant risk of harm?

Ernie Davis: Well, the problem is that without more work on artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence poses no risk. And the distinction between work on AI, and work on AI safety—work on AI is an aspect of work on AI safety. So I’m not sure it’s a well-defined question.

But that’s a bit of a debate. What we mean is, if we get rid of all the AI safety institutes, and don’t worry about the regulation, and just let the powers that be do whatever they want to do, will advanced AI be a significant threat? There is certainly a sufficiently significant probability of that, but almost all of that probability has do with its misuse by bad actors.

The problem that AI will autonomously become a major threat, I put it at very small. The probability that people will start deploying AI in a destructive way and causing serious harm, to some extent or other, is fairly large. The probability that autonomous AI is going to be one of our major problems within the next two hundred years I think is less than one in a hundred.

Robert Long: Ah, good. Thank you for parsing that question. It’s that last bit that I’m curious about. And what do you think are the key things that go into that low probability? It seems like there’s two parts: odds of it being a problem if it arises, and odds of it arising. I guess what I’m trying to get at is—again, uncertainty in all of this—but do you have hunches or ‘AI timelines’ as people call them, about how far away we are from human level intelligence being a real possibility?

Ernie Davis: I’d be surprised—well, I will not be surprised, because I will be dead—but I would be surprised if AI reached human levels of capacity across the board within the next 50 years.

Robert Long: I suspect a lot of this is also found in your written work. But could you say briefly what you think are the things standing in the way, standing in between where we’re at now in our understanding of AI, and getting to that—where the major barriers or confusions or new discoveries to be made are?

Ernie Davis: Major barriers—well, there are many barriers. We don’t know how to give computers basic commonsense understanding of the world. We don’t know how to represent the meaning of either language or what the computer can see through vision. We don’t have a good theory of learning. Those, I think, are the main problems that I see and I don’t see that the current direction of work in AI is particularly aimed at those problems.

And I don’t think it’s likely to solve those problems without a major turnaround. And the problems, I think, are very hard. And even after the field has turned around I think it will take decades before they’re solved.

Robert Long: I suspect a lot of this might be what the book is about. But can you say what you think that turnaround is, or how you would characterize the current direction? I take it you mean something like deep learning and reinforcement learning?

Ernie Davis: Deep learning, end-to-end learning, is what I mean by the current direction. It is very much the current direction. And the turnaround, in one sentence, is that one has to engage with the problems of meaning, and with the problems of common sense knowledge.

Robert Long: Can you think of plausible concrete evidence that would change your views one way or the other? Specifically, on these issues of the problem of safety, and what if any work should be done.

Ernie Davis: Well sure, I mean, if, on the one hand, progress toward understanding in a broad sense—if there’s startling progress on the problem of understanding then my timeline changes obviously, and that makes the problem harder.

And if it turned out—this is an empirical question—if it turned out that certain types of AI systems inherently turned toward single minded pursuit of malevolence or toward their own purposes and so on. And it seems to me wildly unlikely, but it’s not unimaginable.

Or of course, if in a social sense—if people start uncontrollably developing these things. I mean it always amazes me the amount of sheer malice in the cyber world, the number of people who are willing to hack systems and develop bugs for no reason. The people who are doing it to make money is one thing, I can understand them. The people do it simply out of the challenge and out of the spirit of mischief making—I’m surprised that there are so many.

Robert Long: Can I ask a little bit more about what progress towards understanding looks like? What sort of tasks or behaviors? What does the arxiv paper that demonstrates that look like? What’s it called, and what is is the program doing, where you’re like, “Wow, this is this is a huge stride.”

Ernie Davis: I have a paper called “How to write science questions that are easy for people and hard for computers.”8 So once you get a response paper to that: “My system answers all the questions in this dataset which are easy for people and hard for computers.” That would be impressive. If you have a program that can read basic narrative text and answer questions about it or watch a video and answer questions, a film and answer questions about it—that would be impressive.

Notes

- Davis, Ernest. “Ethical guidelines for a superintelligence.” Artificial Intelligence 220 (2015): 121-124.

- Bostrom, Nick. Superintelligence: Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford University Press (2014).

- see, for example, Russell, Stuart. “Provably beneficial artificial intelligence.” Exponential Life, The Next Step (2017).

- Pinker, Steven. “We’re Told to Fear Robots. But Why Do We Think They’ll Turn on Us?” Popular Science 13 (2018).

- This is not an accurate paraphrase because the review in question stipulates that the human could take back “all the 21st-century knowledge and technologies they wanted”. The passage is: “If we sent a human a thousand years into the past, equipped with all the 21st-century knowledge and technologies they wanted, they could conceivably achieve dominant levels of wealth and power in that time period.”—Bensinger, Rob. “Davis on AI Capability and Motivation.” Accessed August 23, 2019. https://intelligence.org/2015/02/06/davis-ai-capability-motivation/.

- Davis, Ernest. “The Singularity and the State of the Art in Artificial Intelligence: The technological singularity.” Ubiquity 2014, no. October (2014): 2.

- Davis, Ernest, and Gary Marcus. “Commonsense reasoning and commonsense knowledge in artificial intelligence.” Commun. ACM 58, no. 9 (2015): 92-103.

- Davis, Ernest. “How to write science questions that are easy for people and hard for computers.” AI magazine 37, no. 1 (2016): 13-22.