By Katja Grace, 17 May 2016

Can AI researchers say anything useful about when strong AI will arrive?

Back in 2012, Stuart Armstrong and Kaj Sotala weighed in on this question in a paper called ‘How We’re Predicting AI—or Failing To‘. They looked at a dataset of predictions about AI timelines, and concluded that predictions made by AI experts were indistinguishable from those of non-experts. (Which might suggest that AI researchers don’t have additional information).

As far as I can tell—and Armstrong and Sotala agree—this finding is based on an error. Not a fundamental philosophical error, but a spreadsheet construction and interpretation error.

The main clue that there has been a mistake is that their finding is about experts and non-experts, and their public dataset does not contain any division of people into experts and non-experts. (Hooray for publishing data!)

As far as we can tell, the column that was interpreted as ‘is this person an expert?’ was one of eight tracking ‘by what process did this person arrive at a prediction?’ The possible answers are ‘outside view’, ‘noncausal model’, ‘causal model’, ‘philosophical argument’, ‘expert authority’, ‘non-expert authority’, ‘restatement’ and ‘unclear’.

Based on comments and context, ‘expert authority’ appears to mean here that either the person who made the prediction is an expert who consulted their own intuition on something without providing further justification, or that the predictor is a non-expert who used expert judgments to inform their opinion. So the predictions not labeled ‘expert authority’ are a mixture of predictions made by experts using something other than their intuition—e.g. models and arguments—and predictions made by non-experts which are based on anything other than reference to experts. Plus restatements and unclarity that don’t involve any known expert intuition.

The reasons to think that the ‘expert authority’ column was misintepreted as an ‘expert’ column are A) that there doesn’t seem to be any other plausible expert column, B) that the number of predictions labeled with ‘expert authority’ is 62, the same as the number of experts Armstrong and Sotala claimed to have compared (and the rest of the set is 33, the number of non-experts they report), and C) Sotala suggests this is what must have happened.

How bad a problem is this? How badly does using unexplained expert opinion as a basis for prediction align with actually being an expert?

Even without knowing exactly what an expert is, we can tell the two aren’t all that well aligned because Armstrong and Sotala’s dataset contains many duplicates: multiple records of the same person making predictions in different places. All of these people appear at least twice, at least once relying ‘expert authority’ and at least once not: Rodney Brooks, Ray Kurzweil, Jürgen Schmidhuber, I. J. Good, Hans Moravec. It is less surprising that experts and non-experts have similar predictions when they are literally the same people! But multiple entries of the same people listed as experts and non-experts only accounts for a little over 10% of their data, so this is not the main thing going on.

I haven’t checked the data carefully and assessed people’s expertise, but here are other names that look to me like they fall in the wrong buckets if we intend ‘expert’ to mean something like ‘works/ed in the field of artificial intelligence’: Ben Goertzel (not ‘expert authority’), Marcus Hutter (not ‘expert authority’), Nick Bostrom (‘expert authority’), Kevin Warwick (not ‘expert authority’), Brad Darrach (‘expert authority’).

Expertise and ‘expert authority’ seem to be fairly related (there are only about 10 obviously dubious entries, out of 95—though 30 are dubious for other reasons), but not enough to take the erroneous result as much of a sign about experts I think.

On the other hand, it seems Armstrong and Sotala have a result they did not intend: predictions based on expert authority look much like those not based on expert authority. Which sounds interesting, though given the context is probably not surprising: whether someone cites reasons with their prediction is probably fairly random, as indicated by several people basing their predictions on expert authority half of the time. e.g. Whether Kurzweil mentions hardware extrapolation on a given occasion doesn’t vary his prediction much. A worse problem is that the actual categorization is ‘most non-experts’ + ‘experts who give reasons for their judgments’ vs. ‘experts who don’t mention reasons’ + ‘non-experts who listen to experts’, which is pretty random, and so hard to draw useful conclusions from.

We don’t have time right now to repeat this analysis after actually classifying people as experts or not, even though it looks straightforward. We delayed some in the hope of doing that, but it looks like we won’t get to it soon, and it seems best to publish this post sooner to avoid anyone relying on the erroneous finding.

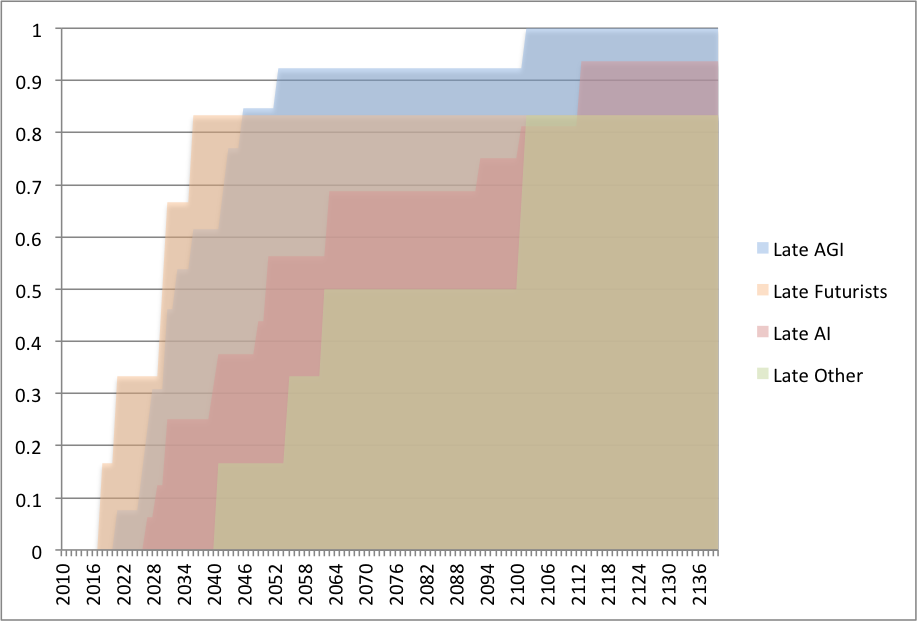

In the meantime, here is our graph again of predictions from AI researchers, AGI researchers, futurists and other people—the best proxy we have of ‘expert vs. non-expert’. We think they look fairly different, though they are from the same dataset that Armstrong and Sotala used (though an edited version).

Stuart Armstrong adds the following analysis, in the style of the graphs on figure 18 of their paper that it could replace:

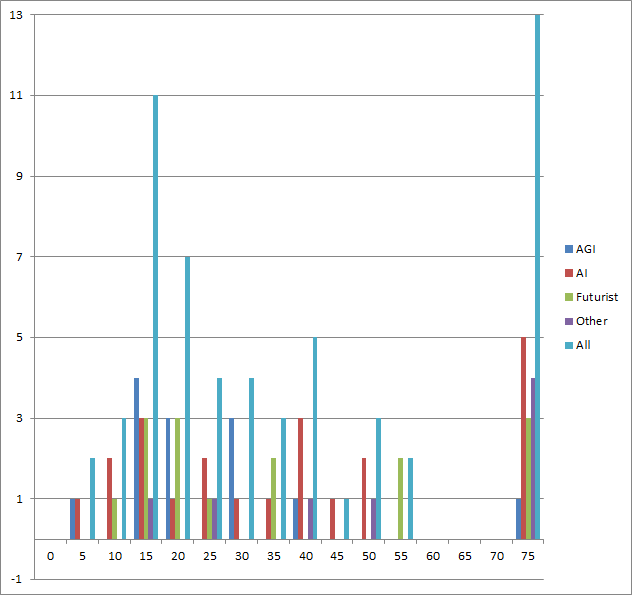

Also please forgive the colour hideousness of the following graph:..Here I did a bar chart of “time to AI after” for the four groups (and for all of them together), in 5-year bar increments (the last bar has all the 75 year+ predictions, not just 75-80). The data is incredibly sparse, but a few patterns do emerge: AGI are optimistic (and pretty similar to futurists), Others are pessimistic..However, to within the limits of the data, I’d say that all groups (apart from “other”) still have a clear tendency to predict 10-25 years in the future more often than other dates. Here’s the % predictions in 10-25 years, and over 75 years:.

%10-25 %>75 54% 8% AGI 27% 23% AI 47% 20% Futurist 13% 50% Other 36% 22%

Thanks for this post! I’m curious how you came to notice this error. It might be helpful to know the thought processes that got you to finding it, so as to catch such errors more quickly and reliably in the future.

I’m afraid I don’t remember well. I used their data for a whole lot of other stuff (see aiimpacts.org/miri-ai-predictions-dataset/) so I looked over it relatively thoroughly in the process. Possibly I was trying to write a page here summarizing what is known about experts and non-experts, and I wanted to check what their results on that would look like if you removed all the data points that we removed, so I was looking for the part of the spreadsheet that would show that, and couldn’t find one (I don’t actually remember, but my guess is something like that).

Good work!

Though I don’t see the graph included in my comment (looking at this via mobile).

Here’s a link for the graph, for those who can’t see it: https://dl.dropboxusercontent.com/u/23843264/Permanent/time_to_AI_decomposed.png

Thanks, and sorry for the error. It should be fixed now.