Published 3 April 2020

In a 10-20 hour exploration, we did not find clear examples of ‘prescient actions’—specific efforts to address severe and complex problems decades ahead of time and in the absence of broader scientific concern, experience with analogous problems, or feedback on the success of the effort—though we found six cases that may turn out to be examples on further investigation.

Details

We briefly investigated 20 leads on historical cases of actions taken to eliminate or mitigate a problem a decade or more in advance, evaluating them for their ‘prescience’. None were clearly as prescient as the actions of Leó Szilárd, which were previously the best examples of such actions that we found. The primary ways in which these actions failed to exhibit prescience were the amount of feedback that was available while developing a solution and the number of years in advance of the threat that the action was taken. Although we are uncertain about most of the cases, we believe that six of them are promising for future investigation.

Background

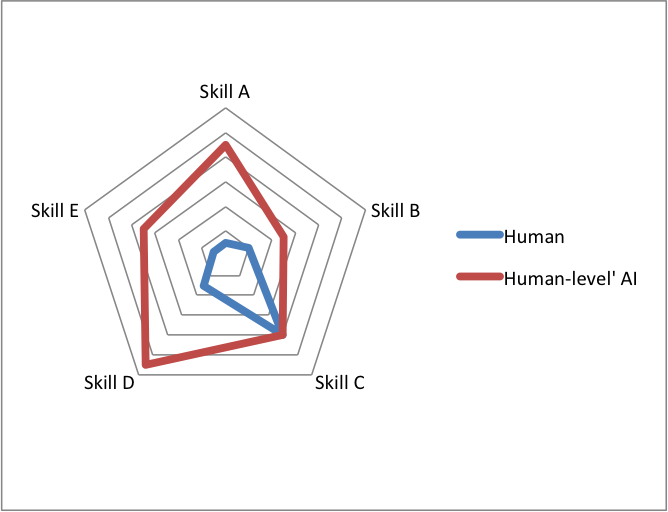

Current efforts to prepare for the impacts of artificial intelligence have several features that could make them unlikely to succeed. They typically require us to make complex predictions about novel threats over a timescale of decades, and many of these efforts will receive little feedback on whether they are on the right track, receive little input from the larger scientific community, and produce results that are not useful outside the problem of mitigating AI risk.

It may be useful to search for past cases of preparations that have similar features. It is important to know if humanity has failed to solve problems in advance because the attempts to do so have failed or because solutions were not attempted. If we find failed attempts, we want to know why they failed. For example, if it turns out that most previous actions were not successful because of failure to accurately predict the future, we may want to focus more of our efforts on forecasting. To this end, we use the following set of criteria for evaluating past efforts for their ‘prescience’, or the extent to which they represent early actions to mitigate a risk in absence of feedback:1

- Years in Advance: How many years in advance of the expected emergence of the threat was the action taken?

- Novelty: Was the threat novel, or can we re-use (perhaps with modification) the solution to past threats?

- Scientific Concern: Was the effort to address the threat endorsed by the larger scientific community?

- Complex Prediction: Did the solution require a complex prediction, or is the solution clear and closely related to the problem?

- Specificity: Was the solution specific to the threat or is it something that is broadly useful and may be done anyway?

- Feedback: Was feedback available while developing a solution, so that we can make mistakes and learn from them, or will we need to get it right on the first try?

- Severity: Was it a severe threat of global importance?

In addition to these criteria, we took note of whether the outcome of the efforts is known, as cases with a known outcome may be more informative and more fruitful for further investigation.

Methodology

Potential cases of interest were found by searching the Internet, asking our friends and colleagues, and offering a bounty on promising leads. We compiled a list of topics to research that were sufficiently narrow to allow for evaluation over a short period of time. This list included individual people that took actions (like Clair Patterson), specific actions that were taken (e.g. the installation of the Moscow-Washington Hotline), and the threats themselves (such as the destruction of infrastructure by a geomagnetic storm).

One researcher spent approximately 30 minutes reviewing each case, and rated them on a scale of 0 to 10 on the criteria described in the previous section.2 A score of 1 indicates the criterion described the case very poorly, while a score of 10 indicates the case demonstrated the criterion extremely well. These ratings were highly subjective, though we made efforts to evaluate the cases in a way that is consistent and which would avoid too many false negatives.3 A composite score was calculated from these by taking a weighted average with the following weights:4

Criterion Weight Number of years in advance5 20 Overall severity of threat 2 Novelty of threat/solution 3 Overall level of concern from the scientific community at large 2 Complexity of prediction required to produce a solution 5 Specificity of solution 2 Level of feedback available while developing a solution 10

In addition to these ratings, we rated each one for how promising it was for further research, and annotated the ratings in the spreadsheet as seemed appropriate. We also assigned ratings to two cases that were previously the subject of in-depth investigations, for comparison. These were the Asilomar Conference and the actions of Leó Szilárd.

Results

The following table shows our ratings. The two reference cases are in italics. Our full spreadsheet of ratings and notes can be found here.

| Case | Score | Suitability for Further Research |

| Leo Szilard | 7.24 | |

| Antibiotic resistance | 7.11 | 7 |

| Open Quantum Safe | 6.80 | 5 |

| Nordic Gene Bank | 6.74 | 4 |

| Geomagnetic Storm Prep | 6.74 | 5 |

| Fukushima Daichii | 6.74 | 5 |

| Swiss Redoubt | 6.60 | 2 |

| Nonproliferation Treaty | 6.14 | 6 |

| Cavendish Banana and TR4 | 6.12 | 5 |

| WIPP | 6.02 | 4 |

| Population Bomb | 5.99 | 3 |

| Y2k | 5.76 | 4 |

| Asilomar Conference | 5.70 | |

| Cold War Civil Defense | 5.29 | 3 |

| Religious Apocalypse | 4.88 | 2 |

| Hurricane Katrina | 4.18 | 4 |

| Iran Nuclear Deal | 4.18 | 4 |

| Moscow-Washington Hotline | 3.90 | 3 |

| England 1800s Policy Reform | 3.89 | 2 |

| Clair Patterson | 3.74 | 2 |

| Missile gap | 3.22 | 2 |

| PQCrypto Conference 2006 | 4 |

For one case, the PQCrypto 2006 conference, we were unable to find sufficient information after 45 minutes of investigation to provide an evaluation.

In general the cases we investigated did not score highly on these criteria. The average score was 5.6 out of 10, with the US-Russia missile gap receiving the minimum score of 3.0 and antibiotic resistance receiving the maximum score of 7.11. None of the cases received a higher score than our reference case, the actions of Leó Szilárd (score = 7.24), which we consider to be sufficiently ‘prescient’ to be worth examining. Just over half (11) of our cases received higher ratings than the Asilomar Conference (rating = 5.6), which was previously judged to be less prescient.

The ratings are highly uncertain, as is natural for thirty minute reviews of complex topics. On average, our 90th percentile estimates were 80% larger than their corresponding 10th percentile estimate. All but four cases had minimum ratings lower than the best guess for Asilomar, and more than half had maximum ratings higher than the best guess for Leó Szilárd.

The axes on which the cases were least prescient were feedback and years in advance.6 The cases were most analogous on severity, novelty, and specificity of solution, losing on average .20, .30, and .20 points from their composite scores, respectively.

Two cases, antibiotic resistance and the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, seemed particularly promising for additional research, and received scores of 7 and 6 accordingly. Five other cases received scores of at least five and seemed less promising, but likely worth some additional research.

Discussion

Although the very short research time allotted to each case limits our ability to confidently draw conclusions, we ruled out some cases which were clearly not prescient, identified some promising cases, and roughly characterized some ways in which efforts to reduce AI risk may be different from past efforts to reduce risks.

Irrelevant Cases

There were four cases that we found to be poor examples of prescient actions: The US-Russia Missile Gap of the late 1950’s, the actions of Clair Patterson to combat the use of leaded gasoline, 19th century policy reforms in England that were made in response to the industrial revolution, and the Moscow-US Nuclear Hotline. All of these cases involved actions that were taken in response to, rather than in anticipation of, the emergence of a problem (or perceived problem), and for which the solutions were relatively straightforward, with the primary barriers being political.7

Questionable Cases

Two cases involved actions based on highly dubious predictions: Preparations for a religious apocalypse8 and the book The Population Bomb and the accompanying actions of author Paul Erhlich. Although the actors in these cases were acting on predictions that have since been shown to be inaccurate, the cases do have some similarity to AI risk. They were addressing predictions of severe consequences from novel threats, they were acting without help from the scientific community, and they did not expect to receive a great deal of feedback along the way. However, the actions were only taken 5-10 years in advance of the threat, and we expect the apparent disconnect between the forecasts and reality to make it more difficult to learn from the actions.

Some cases involved threats that had already emerged, in the sense that they could happen immediately, but had sufficiently low per-year risk for a reasonable person to expect the outcome to be at least a decade in the future. These include Hurricane Katrina, US civil defense during the cold war, Fukushima Daichii, the comparison case Asilomar Conference, and the Nordic Gene Bank.9 10

Other cases involved solutions that were easy or not dependent on complex forecasting. The Swiss National Redoubt relied on long-range forecasting, but was more of a large investment in defense than a complex search for a solution. The year 2000 problem was easy to address, even without taking action until relatively shortly before the event took place. The Iran Nuclear Deal (and perhaps also the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty) required difficult political negotiations, but did not appear to rely on complex predictions.

Promising Cases

We identified six cases that seem promising for further investigation:

Alexander Fleming warned, in his 1945 Nobel Lecture, that widespread access to antibiotics without supervision may lead to antibiotic resistance.11 We are uncertain of the impact of Fleming’s warning, whether he took additional action to mitigate the risk, or how widespread within the scientific community such concerns were, but our impression is that it was not a widely known issue, that his was an early warning, and that his judgement was generally taken seriously by the time of his speech. His warning preceded the first documented cases of penicillin-resistant bacteria by more than 20 years, and the threat of antimicrobial resistance seems to be broadly analogous with AI risk on most of our criteria, though it does seem that feedback was available throughout efforts to reduce the threat.

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons required many actions from many actors, but it seems to have required a complex prediction about technological development and geopolitics to address a severe threat, was specific to a particular threat, and had limited opportunities for feedback. We are uncertain if any of the specific actions will prove to be prescient on further investigation, but it seems promising.

Open Quantum Safe is an open-source project to develop cryptographic techniques that are resistant to the use of quantum computers. The threat of quantum computing to cryptography has several relevant features, including complex forecasting over a decades-time scale of a novel threat. We found limited information on the circumstances surrounding the founding of the project or the related case, the 2006 PQCrypto Conference, but the problem generally seems prescient.

Geomagnetic Storm Preparation addresses the threat caused by severe damage and disruption by solar weather to electronics and power infrastructure, which could be a severe global catastrophe.12 The expected time between such events is decades or centuries, and mitigating the risk involves actions that may be specific to the particular problem and requires complex predictions about the physics involved and how our infrastructure and institutions would be able to respond. However, we are uncertain about which actions were taken and when, and whether there is evidence that they are working. Additionally, there is substantial investment from the scientific community and we are uncertain how much feedback is available while developing solutions.

Panama Disease is a fungal infection that has been spreading globally for decades and threatens the viability of the cavendish banana as a commercial crop. Cavendish bananas account for the vast majority of banana exports, and are integral to the food security of countries such as Costa Rica and Guatemala.13 Early action included measures to slow the spread of the fungus, a search for cultivars to replace the Cavendish, calls for greater diversity in banana varietals, and searches for fungicides that are able to kill the fungus. Although these actions have many opportunities for feedback, some of them involve complex predictions and searches for specific technical solutions, and, from the perspective of farmers on continents that have not yet encountered the infection, the arrival of the fungus represents a discrete event at some undetermined time in the future. We are uncertain if these are good examples of prescient actions, but they may be worth additional investigation.

Presence of Feedback

The axis on which our cases most differed from efforts to reduce AI risk was the level of feedback available while developing a solution. The average score on feedback was 3.8, and none of the cases received a score higher than 7. Even cases that initially seemed that they would have very little feedback proved to have enough to aid those that were making preparations. Examples include Hurricane Katrina, which benefited from lessons learned from preceding hurricanes, and the National Redoubt of Switzerland, which benefited from the observation of conflicts between other actors, providing information about which military equipment and tactics were viable against likely adversaries. Assuming that these results are representative, here are two ways to interpret these results:

Feedback is abundant: Feedback is abundant in a wide variety of situations, so that we should also expect to have opportunities for feedback while preparing for advanced artificial intelligence. In support of this view are the cases mentioned above that were initially expected to lack feedback, even on the part of those making preparations, but which nonetheless benefited from feedback.

AI risk is unusual: The common perception that there is very little feedback available to efforts to reduce the risks of advanced AI is correct, and AI risk is unique (or very rare) in this regard. Support for this view comes from arguments for the one-shot nature of solving the AI control problem.14

Primary author: Rick Korzekwa

Notes

- Originally proposed by Alexander Berger in 2015.

- All of the ratings were assigned by Rick Korzekwa

- For example, efforts to reduce the risks of geomagnetic storms and antibiotic resistance both involve some actions that are high in specificity and others that are low in specificity. We evaluated both cases on the most specific-to-the-problem actions that we are aware of.

- Because we were highly uncertain about our scores given only a half hour of research per case, we assigned scores for our best guess, or ‘median guess’ score, as well as 10th and 90th percentile estimates for each criterion for each case. These should be interpreted as the range of scores which we expect we would arrive at given several hours of investigation, with 80% credence, and equal likelihood of having over- or underestimated the score. We calculated 10th and 90th percentile estimates of the average by modeling the high and low estimates as uncorrelated deviations from the mean, so that they could be added in the usual way for propagating uncorrelated errors.

- This score was calculated directly from the estimated number of years by a root logistic function with values 2.75, 7.1, and 9.6 for 0, 10, and 20 years, respectively

- On average, the cases lost 1.35 points from their composite score on each of these criteria. This is partly due to the large weight assigned to these criteria. If we used an unweighted average to compute the scores, cases would lose .77 points for feedback and .39 for years in advance, with years in advance being the axis with the highest average score.

- Clair Patterson made some impressive inferences about the present state of the world, and seemed to believe that the problems he was observing would continue to get worse without intervention. In this respect, his actions were prescient. But in general, he was working to prevent a present problem from becoming worse, rather than working to avoid a future problem.

- Preparations for religious apocalypse is a broad category. We attempted to find examples in this category that fell within our target reference class, but we were generally unable to find examples that involved specific actions taken more than a few years in advance. We are not highly confident that there do not exist examples that meet these criteria.

- The Nordic Gene Bank addresses a low per-year risk, so that it seems reasonable to consider it to be addressing a future risk. However, the first withdrawal from the seed vault happened relatively quickly, suggesting that either the risk is near term or that the solution is not highly specific to long term risks.

- Although geomagnetic storm preparation has a similar quality, it seems that the per-year risk of a catastrophic outcome is low enough, and the preparations for such severe outcomes is specific enough that it qualifies as a promising case, as described in the next section.

- “The time may come when penicillin can be bought by anyone in the shops. Then there is the danger that the ignorant man may easily underdose himself and by exposing his microbes to non-lethal quantities of the drugmake them resistant.” “Wayback Machine,” March 31, 2018. https://web.archive.org/web/20180331001640/https://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/medicine/laureates/1945/fleming-lecture.pdf.

- See, for example https://allfed.info/industrial-civilisation/

- “export revenue from bananas covered 40 percent of Costa Rica’s food import bill and 27 percent of Guatemala’s in 2014” “EST: Banana Facts.” Accessed February 6, 2020. http://www.fao.org/economic/est/est-commodities/bananas/bananafacts/en/#.XjyilyOIYuV.

- For instance, Eliezer Yudkowsky obliquely argues this in The Rocket Alignment Problem. “The Rocket Alignment Problem – Machine Intelligence Research Institute.” Accessed March 26, 2020. https://intelligence.org/2018/10/03/rocket-alignment/.